Two of our team members, Raquel Liceras-Garrido and Katherine Bellamy have recently completed the project ‘Pathways to understanding 16th century Mesoamerican geographies’, funded by the Lancaster University Department of History.

This spin-off project has used ESRI StoryMaps, combining interactive texts, images and maps in a series of online interactive learning resources on the history, archaeology and geography of the Mesoamerican Postclassical and Colonial period of Central Mexico, beginning in the 14th through to the mid-16th century. These resources are divided into three main areas:

The first of the story maps explores the history of the Mexica people, beginning with their journey to the foundation of Tenochtitlan in 1325, which would become (alongside its neighbour city to the north, Tlatelolco) the heart of the Triple Alliance. Following this, the story map shows how the Mexica began to expand, featuring the lists of conquered settlements as recorded in the Codex Mendoza. This leads up to the arrival of the Spanish, and the ultimate meeting of Moctezuma II and Hernán Cortés in 1519. It then proceeds to describe how Cortés, with considerable assistance from his indigenous allies, conquered Tenochtitlan. This story map concludes with a look at the beginning of the colonial era, exploring how the Spanish began to impose their own institutions across ‘New Spain’, with varying success due to the continuing influence of indigenous institutions across Mesoamerica.

This story map explores the nature of historic place-names across what is currently Mexico, introducing the importance of place-names and language as a tool of colonisation and empire. The story map explores how this tool was used not only by the Spanish, but also by the Mexica and the Triple Alliance (not to mention other indigenous groups), as part of their systematic colonisation of conquered settlements and people. The story map goes on to explore how indigenous place-names continued to be used, despite the processes of colonisation at the hands of both the Triple Alliance and the Spanish. In addition, it explores the meaning of Nahua toponymy in particular – demonstrating the use of suffixes such as -tepec (which means ‘inhabited place’) and showing the distribution of some of these examples. Following this are some case studies of individual place-names, explaining their meaning and how they have been depicted in the historical record. The story map concludes by giving a brief overview of colonial naming, and how indigenous influences have continued.

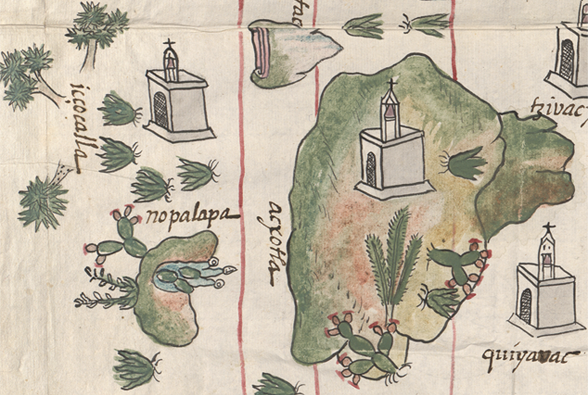

The final story map discusses depictions of geographic space and place. This starts with an explanation of why this is an important discussion, with particular reference to, and problematisation of, the use of Geographic Information Systems for representing historical geographies. Following this, the story map introduces the idea of representations of space, which may be unfamiliar to the modern reader, and explores the various types of pre-Hispanic Nahuatl documents, including those which represented geographies. The story map gives an introduction to the state of Spanish cartography in the sixteenth-century, before going on to discuss how the Spanish and Nahua traditions of depicting geography began to merge during the conquest of Mexico. There is considerable evidence of this merging of traditions throughout the historical record, which the story map explains, giving two specific examples.