A considerable amount of our time on the project so far has been dedicated to GIS, and to the creation of maps which reflect geographic boundaries as they existed in sixteenth century Middle America. The work of Peter Gerhard and Howard F Cline has been an invaluable source of information, providing detailed explorations of the historical geography of New Spain in the years following Spanish arrival.

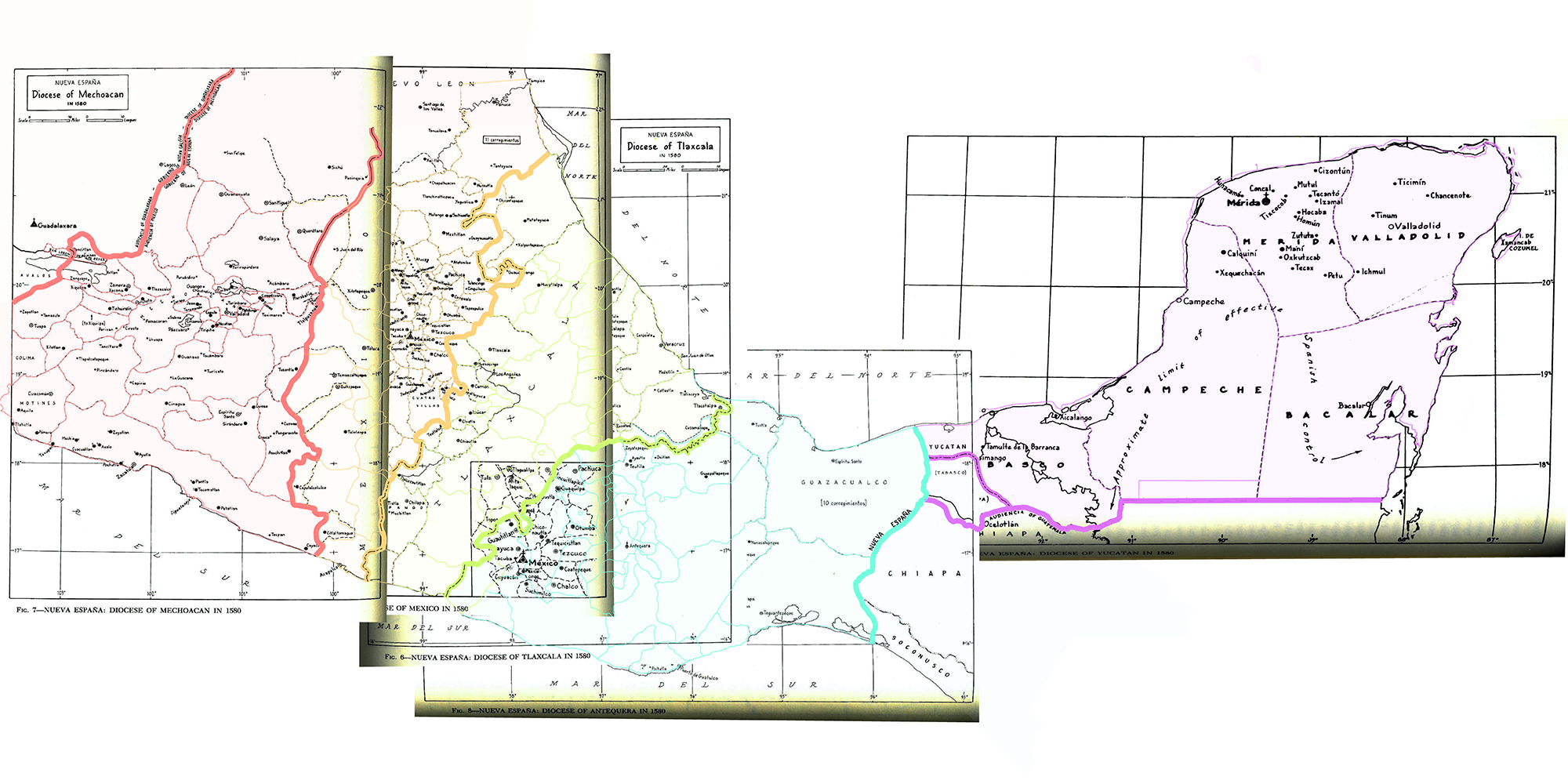

The maps Gerhard produced focused largely on the administrative boundaries imposed by the Spanish in the sixteenth century. We have used these maps as a starting point, creating GIS layers which reflect boundaries as depicted by Gerhard:

Whilst some of these administrative units were built upon pre-existing and well-established indigenous systems of governance, they ultimately reflect a Spanish administrative geography, divided into dioceses, audiencias, and provincias, with identified place-names being the sites of Spanish alcaldia mayores and corregimientos.

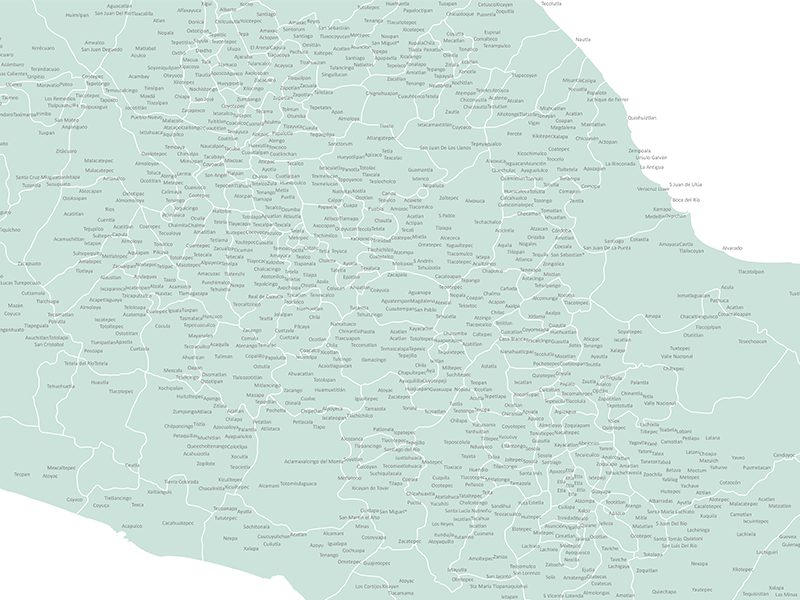

Of course, Middle America’s historical geography did not begin with the establishment of Spanish administrative units, and we aim to produce a more representative image of Middle America’s sixteenth century geography. The identification of historic place-names will be key to our understanding of indigenous and historic geographies, and we are currently creating GIS layers which locate these place-names.

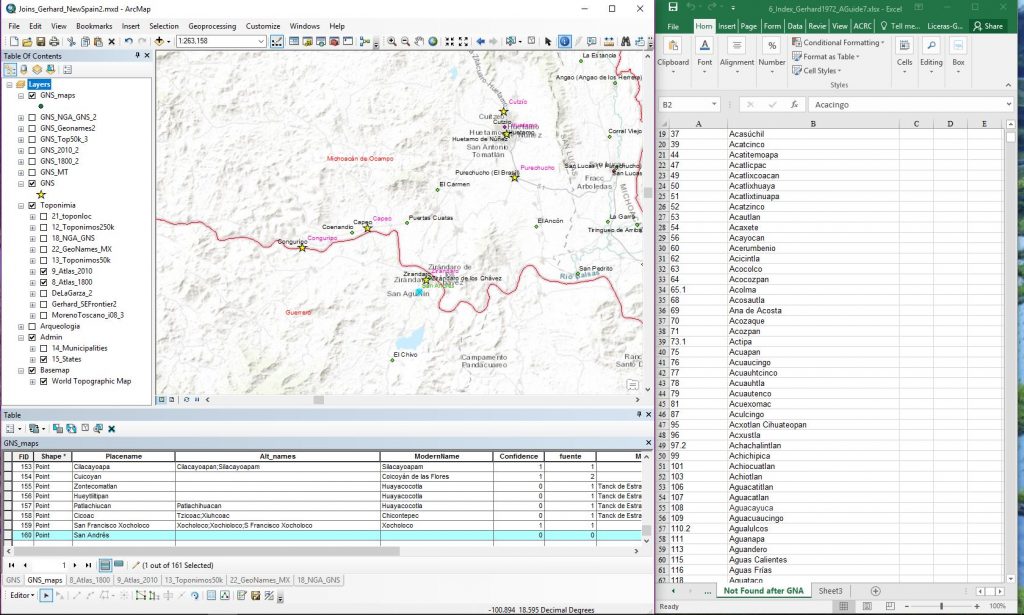

The process for doing this has been straightforward but very time-consuming, as it could only be semi-automated. We began with the digitisation of various geographic indexes included in the works of Peter Gerhard, Mercedes de la Garza, René Acuña, Francisco del Paso y Troncoso and Alejandra Moreno Toscano. These indexes contain thousands of place-names referenced in the Relaciones Geográficas. With these lists compiled, we then had the task of cross-referencing, or joining, these tables with existing location data, derived from a number of sources including historical secondary sources INEGI and Geonames.

Of course, changes over time and variations in spelling mean that joining these sets of data cannot rely solely on a computer recognising identical matches. Our UK Research Associate, Dr Raquel Liceras-Garrido in collaboration with our Mexico Research Associate Mariana Favila-Vázquez, has been spearheading the painstaking task of locating the thousands of place-names for which there was no match with existing geographic data. Already a monumental undertaking, the process is further complicated by the fact that there are often numerous names for the same place (and these numerous names often have numerous alternative spellings!) For example, throughout the historical record, present-day Ixtacamaxtitlán in Puebla state is known variously as San Francisco Iztaquimaxtitlan, S Francisco Iztaquimaxtitlan, Istac-ymachtitlan, Estacquimestitlan, Itztaquimitztitlan and Castilblanco.

Place names are often repeated across America (don’t get us started on San Juan) and there are numerous cases where it is not possible to determine the exact location of a place-name. The expertise of our colleagues in Mexico, Mariana Favila Vázquez and Dr Diego Jimenez-Badillo, has been invaluable in the disambiguation of hundreds of these place-names. For place-names which we have been unable to locate, our Mexican team have undertaken historical research in order to assign them coordinates. For those place-names which have managed to evade all our investigations (for now!), our Mexico team have so far been able to at least determine the region in which they lie.

This research will also prove invaluable in our experiments conducted in collaboration with the Portuguese team on automatic multilingual Named entity Recognition and place-name linguistic and geographic disambiguation, which is the next stage in our research.