by Aleksandra Ianchenko, Cemore Visiting Researcher, 2024.

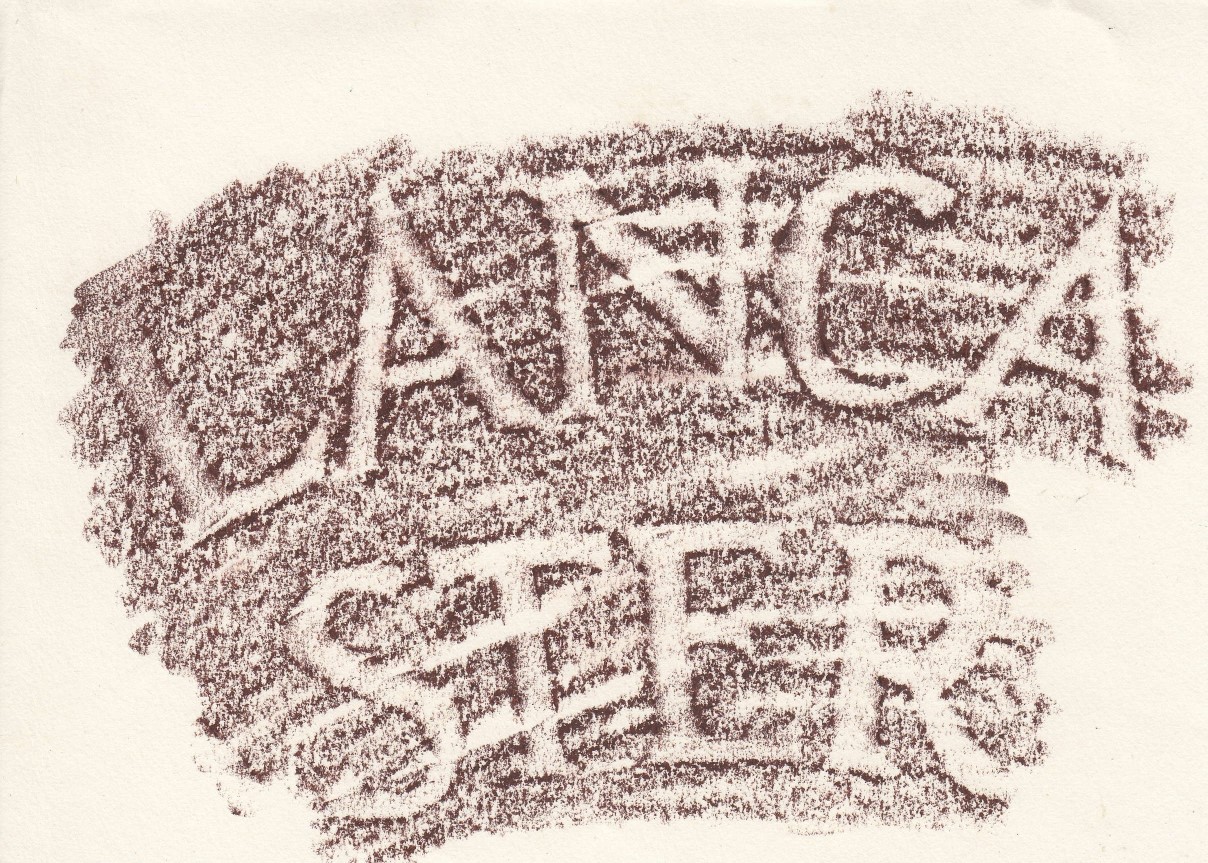

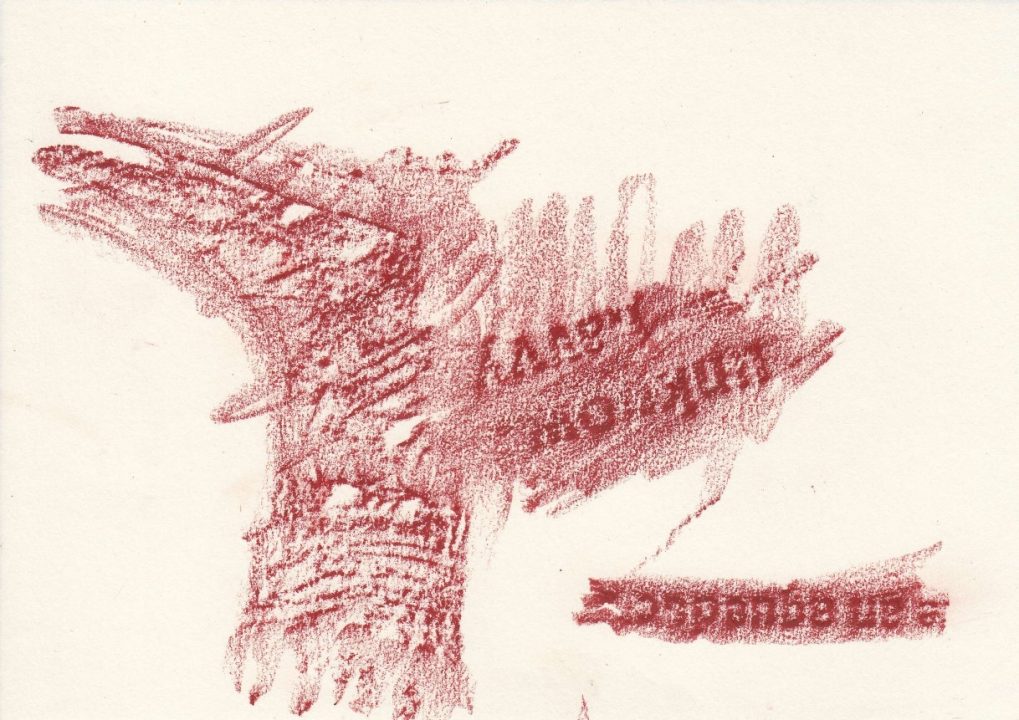

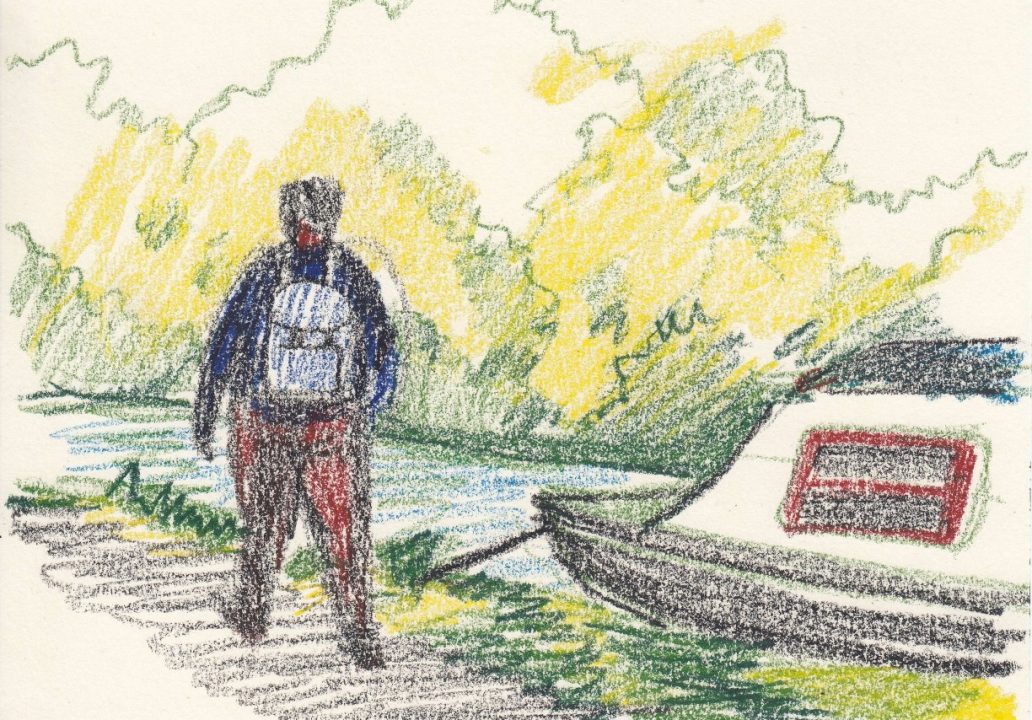

Image: Frottage from the milestone along the Lancaster Canal

In June, I was lucky to be a visiting scholar at the Lancaster Institute for the Contemporary Arts (LICA) and the Centre for Mobilities Research (CEMORE). I am grateful to Lynne Pearce, Professor at the Department of English and Creative Writing and CEMORE’s Co-director, and Jen Southern, Senior Lecturer at LICA and Associate Director of the CEMORE who invited and welcomed me in Lancaster. This research stay was possible thanks to the financial support of the H. W. Donner Foundation Travel Grant.

Upon my arrival, Jen welcomed and briefly showed me the LU Campus which is like a small town with many office and living buildings, cafes, shops, and even hairdressers. She also passed me the key from the CEMORE lab. I was thrilled when I unlocked the door and stepped inside the lab which I have heard about so much!

It was about five years ago when I first browsed the webpage of the Centre. I got so excited that I emailed the Centre introducing my artists practice and my proposal for a future PhD project. I received an encouraging response from Jen who soon after invited me to ARTMOBS newsletter through which I eventually found the PhD position in the PUTSPACE project. Now, I have submitted my thesis for the final defence and am grateful to think what role the Centre played in my career. That is why visiting the Centre and Lancaster University meant a lot for me.

Eightieen days of my stay passed very quickly. I was happy to meet another visiting at that time scholar, Elisa Mozzelin, PhD student from Italy, who is doing a fantastic project to establish a philosophy of walking. Together we participated in the CEMORE Summer Seminar entitled ‘Community, Politics, and Creativity in Mobilities Research’ (chairs: Jen Southern and Lynne Pearce). There, I received stimulating questions and comments from the audience when presenting my paper ‘Walking and Drawing as a Method for Urban Hauntings’. In addition, I got a chance to see LICA’s Degree show and participated in a critical seminar for MA Fine Art students (MA group crits) where I presented my practice and commented on students’ works in progress.

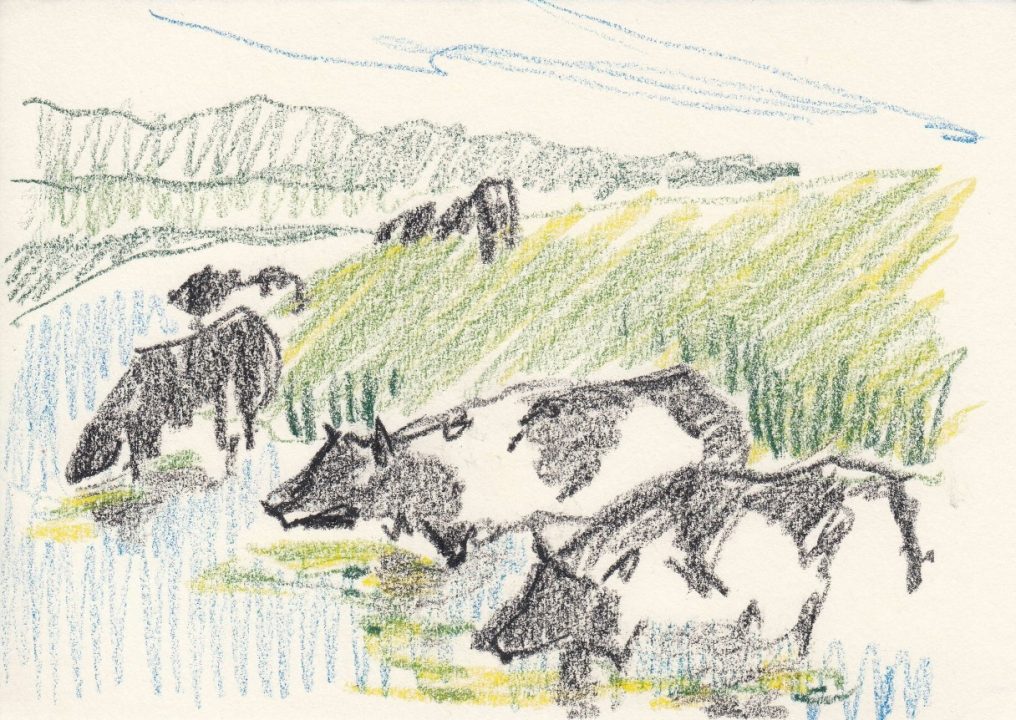

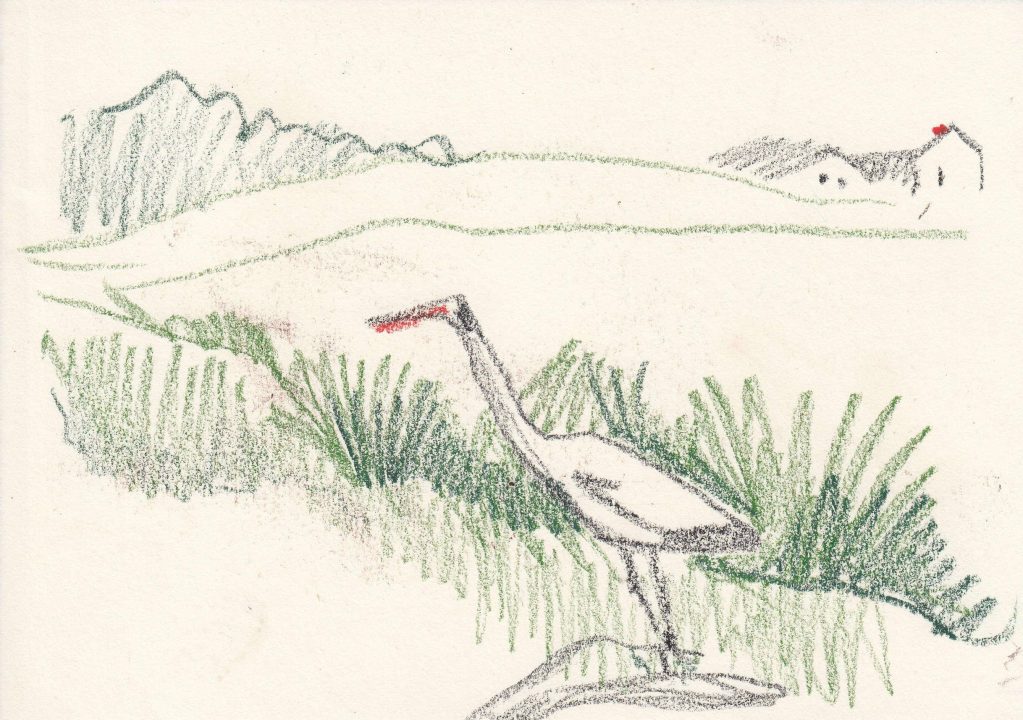

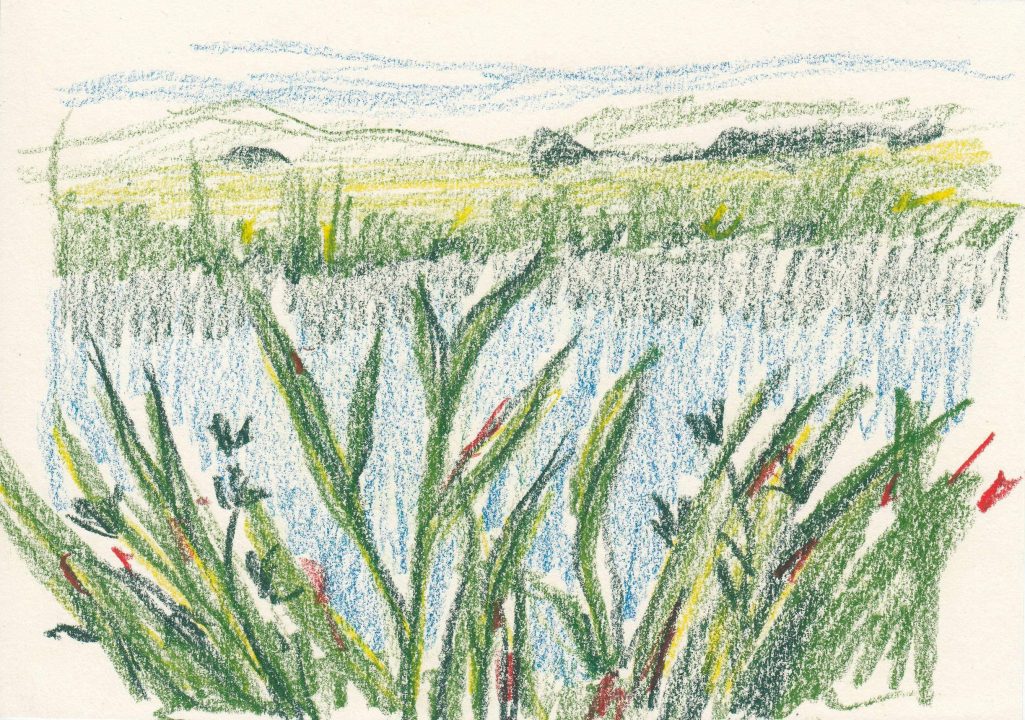

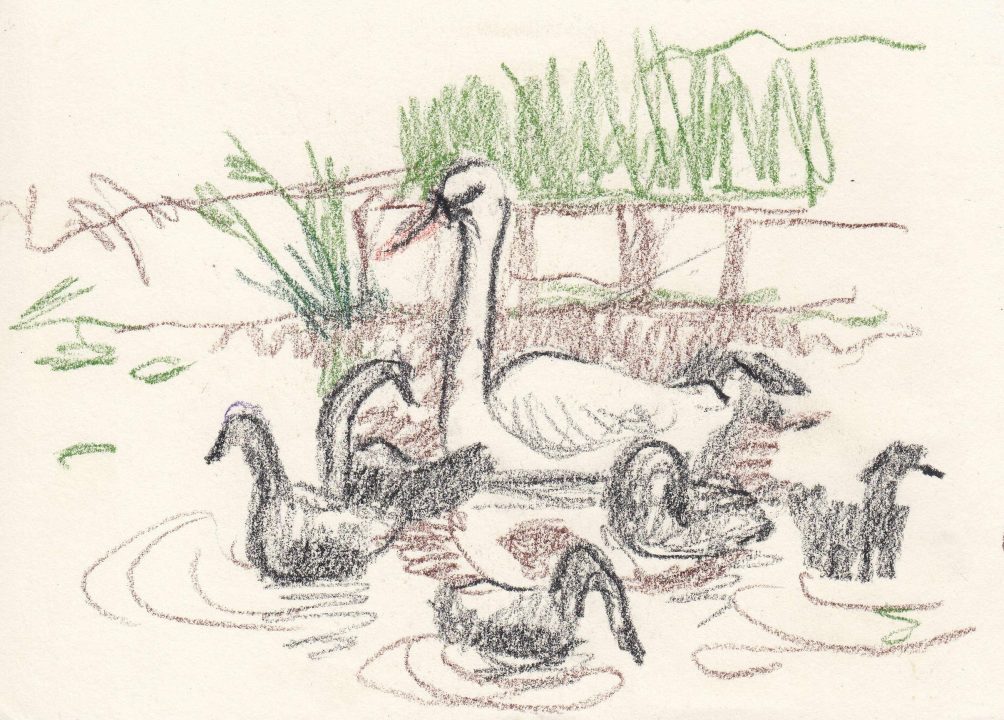

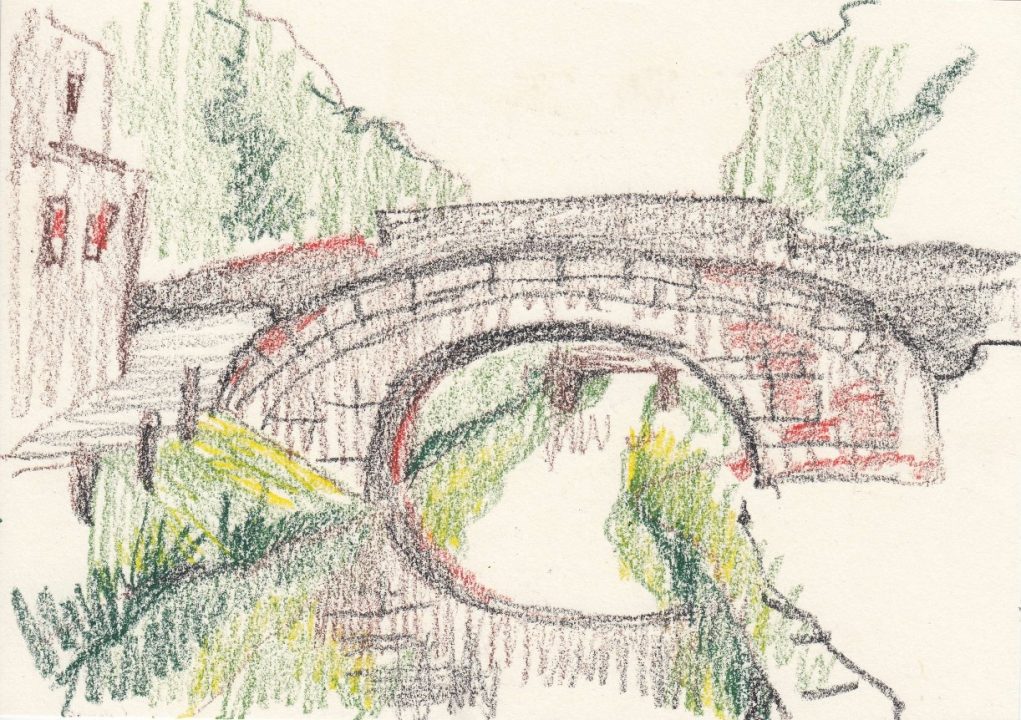

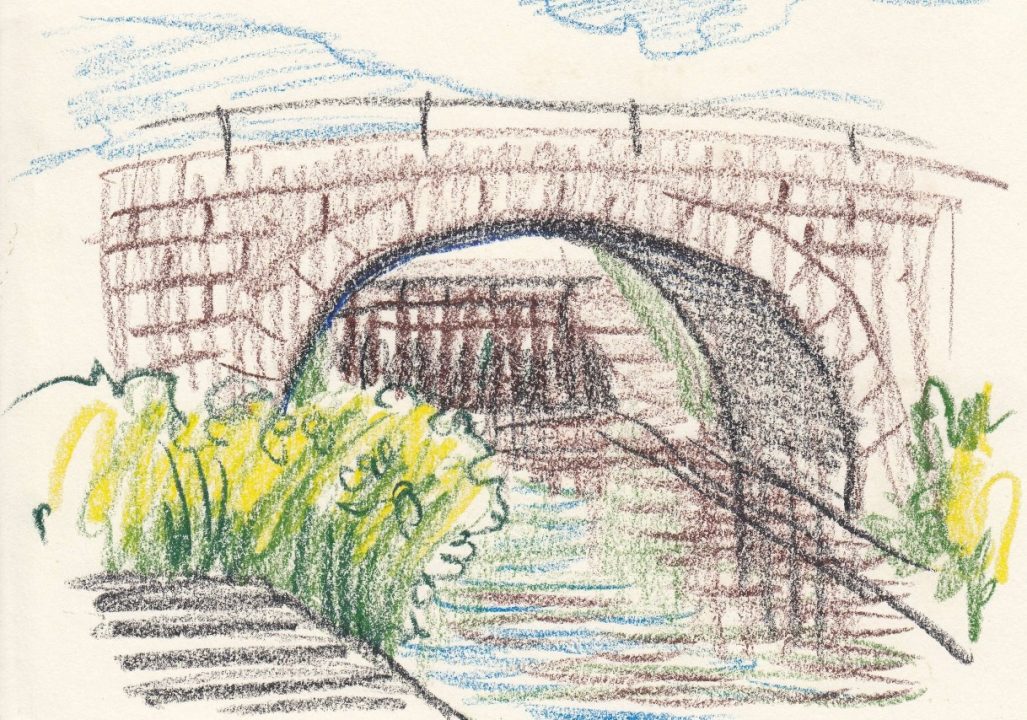

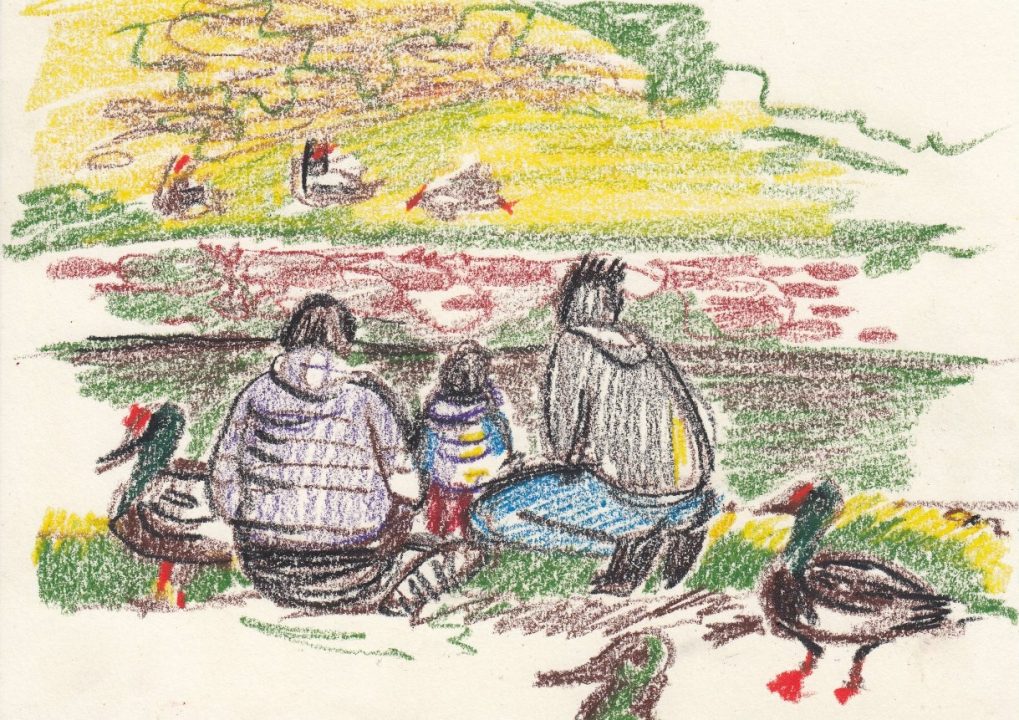

I also got a chance to discover the city of Lancaster. I was surprised that rural and natural areas so close to the city centre: just walk 10 minutes and you are out there in green meadows. In the summertime, this proximity was a bliss and I enjoyed it very much. The most fascinating discovery for me was the Lancaster Canal. I did several walks along the Canal: from the city to the Lune Aqueduct (2,4 miles) and from the Glasson Dock back to the city (11 miles). During my walk, I made sketches with oil pastel.

Observational sketching in situ is one of my art and research methods. It allows you to get ‘attuned’ to the location: physically by positioning your body and moving a hand over paper, sensory by paying attention to sounds and smells around you, and emotionally by establishing a closer connection to the location. Sketching sometimes feels like touching when you palpate objects with your eyes, and examine their shapes and positions. Through this process, objects and scenes become closer, more familiar and intimate. Sketching is always selective. Selecting what to draw helped me process my impressions and experience of the Canal, which was an unknown and exciting place for me.

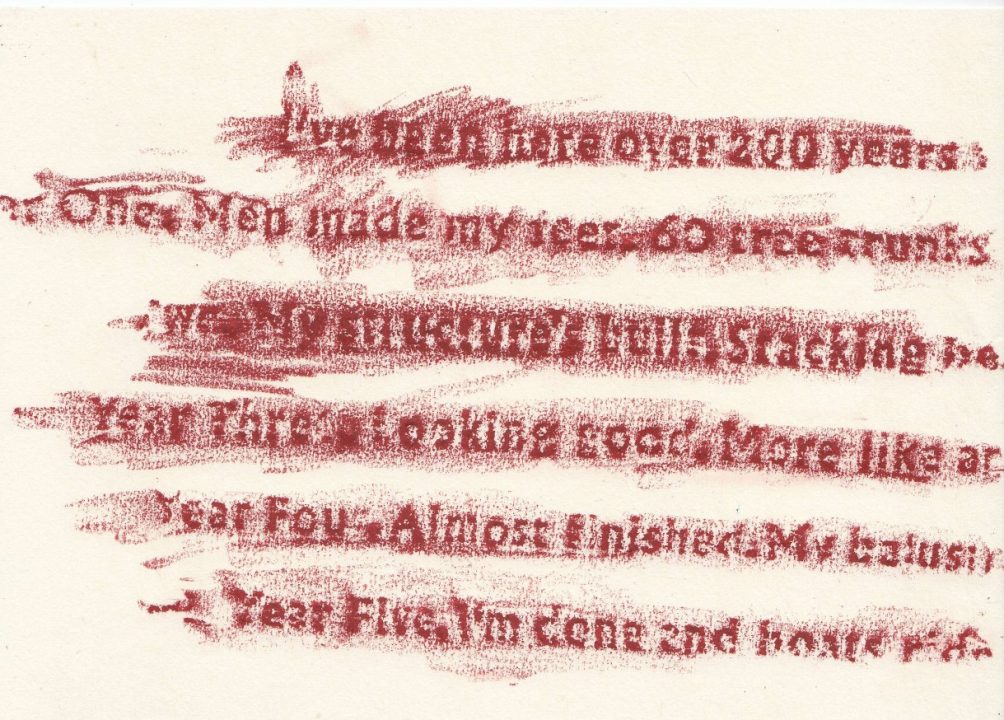

The environment along the canal was very colourful and full of detail. It felt overwhelming, but the limited choice of materials and colours helped me to cope. I mainly used brown and green, with some yellow, blue and orange. The oil pastel, as a soft material, allowed me to vary this palette with different shades, pressing the pastel stick onto the paper with different pressures. The limited colours and tools help to reduce the rich experience of the place to key elements, which in turn helps to develop a coherent series of drawings as one project. In addition to drawing on the canal, I also researched its history, which helped me to understand the place better. In this blog post, I juxtapose quick facts about the canal with my drawings, creating a visual story.

The construction of the Canal started in 1792 to transport goods, limestone from quarries in Kendal, and coal from mines in Bolton. It was an expensive and ambitious project. Due to its costs, there were delays and deviations from the initial design. However, the connection between Kendal and Bolton was created, and the stretch to the Glasson Dock was made in 1826. In 1885 the Canal Company dissolved and the construction finished.

Besides transporting goods, there was also a passenger service by so-called packet boats which operated from 1833 to 1846. Boats were pulled by horses who walked on the towpath along the canal. The speed was about 9 miles per hour and the number of passengers was up to 70. However, the opening of the Lancaster and Carlisle railway put an end to packet boat service. There is a fantastic exhibition about the canal at Lancaster Maritime Museum. One of those boats was called Water Witch. Today, it is the name of the pub on the canal in Lancaster.

The construction of the Canal was an impressive and laborious task. The plan was made by young talented civil engineer John Rennie, whereas construction work was undertaken by diggers or as they were called, navvies. In his fascinating book Building the Lancaster Canal (1979), Robert Philpotts describes their work as low-paid and hard when they had to work ten hours a day for six days a week. Philpotts also describes the construction process:

“The cutters would begin digging along the certain section making a trench about 20’ wide and 7’ deep. When this was done then the bottom and sides had to be made watertight by a process known as puddling. Puddling comprised of filling the bottom and sides of the canal with a waterproof lining of clay and this could vary in thickness…Sometimes it was a yard deep. The clay had to be treaded to make it impervious to water and one method of doing this was to have navvies stamp up and down on it in their bare feet until all the air bubbles were driven out.” (Philpotts, 1979, pp. 23-24).

When the canal was properly padded, the towpath for horses was paved along the canal. Whereas cutters were digging a canal, stonemasons built accommodation bridges above the canal. Today, various bridges are highlights and points of attraction for everyone walking along the canal.

One of the most spectacular objects of the Lancaster Canal is Lune Aquaduct. It was designed by John Rennie and constructed by architect Alexander Stevens. The construction took place between 1794 and 1797. It was an expensive project. For instance, Rennie insisted on using a special volcanic powder, pozzolana, as a mortar, which had to be shipped from Italy. To meet the deadline, the work went around the clock.

Today, on the way to the Aquaduct, one can see a memorial plate. It was designed in 2012 by local artist Rachel Midgley together with Central Lancaster High School. The plate features the portrait of Rennie and notably, a figure of ‘an unknown navvy” whose hard labor enabled this impressive infrastructural object.

Intuitively, I placed a paper onto the plate and rubbed it with an oil pastel. This technique known as rubbing or frottage was popularised by the surrealists Max Ernst who regarded it as a sort of automatic drawing. It could be seen as a type of drawing from life in a very direct sense by literary making a cast of the real object.

The development of the railway (and subsequently motorised transport) downplayed the canal as a transportation channel. Gradually, its role diminished and the last commercial service was carried out in 1947. There were calls for draining and closing the canal, but it eventually it was preserved by the Lancaster Canal Trust formed in 1963. Today, the Canal is a part of the UK canal network. It is used for private and excursion boats, and there are walking and cycling paths along the canal.

The Canal is also a natural habitait for many species. During my walks, I have seen not only domestic sheep, cows and horses herding on meadows along the Canal but also the variety of water birds: ducks, swans, herons. It was great to watch a swan family with seven ducklings swimming down the stream. These ‘encounters’ – places, creatures, or activities – I tried to capture on paper. Later, I have learned that there is a term what what I did – gongoozling. It means watching boats and activities on canals and is similar to trainspotting.