Last week, CeMoRe co-organised the workshop Mobile Utopia. One day of intense play to imagine and develop utopias of everyday life for 2051. Georgia Newmarch reports.

Object-based thinking encourages an exploration of how we place importance on aspects of our daily lives. For the Mobile Utopias workshop, participants were asked to bring an object which represented their mobile Utopia/dystopia. Objects ranged from a small dog (unfortunately not a real one) to an early form of bike light.

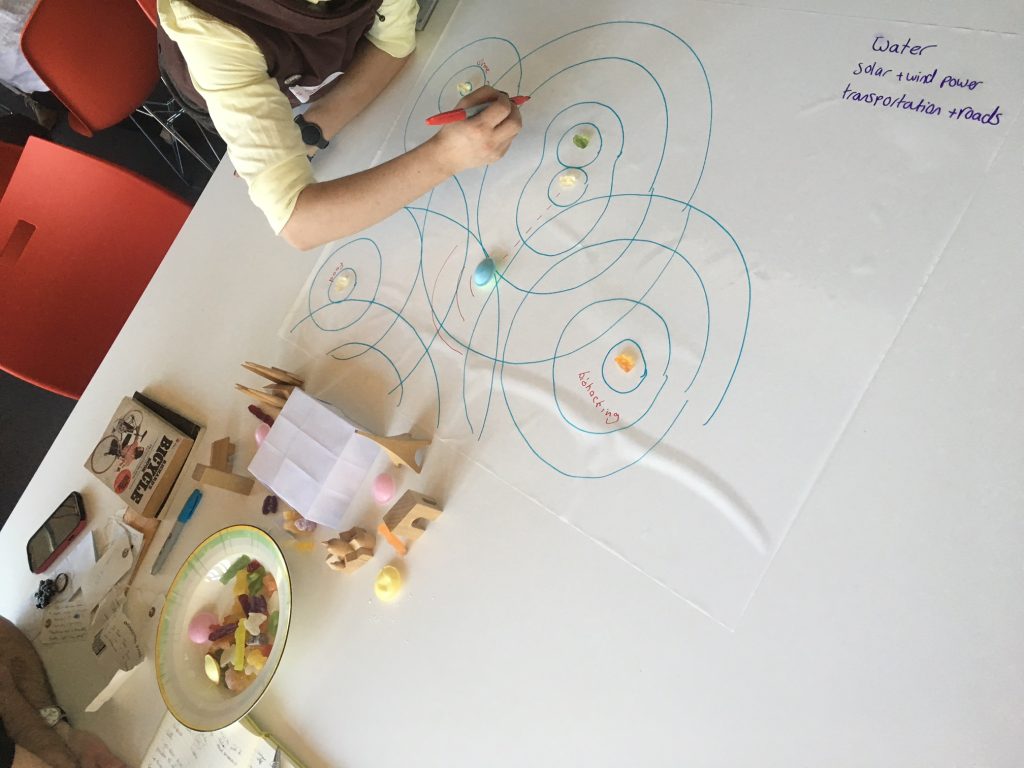

Participants were asked to imagine that they were going to be curating an exhibition in 2051, 200 years after the Great Exhibition of 1851. After discussing the items, participants broke out into four groups, instructed to create a mobile Utopia using a selection of the objects. In addition, various props were provided, including toy cars and jelly babies.

The objects stood out to us as demonstrating how the idea of Utopia is one that is not only given to you, but also created from within.

Using Colin Ward’s 1974 book Utopia, a boarding pass for a flight from Oslo to Manchester, a series of cards by sex activist Maggie Mayhem called Stations of the (Pornographic) Cross, and a bike chain that had been re-purposed into a key ring, my group began to build a Utopia.

The objects stood out to us as demonstrating how the idea of Utopia is one that is not only given to you, but also created from within. Within Utopia, an assessment of needs that are not necessarily visual or tangible is needed – emotional well-being is needed to create it.

Using the tools provided, we created a family who lived within this utopia. A family, not necessarily related to each other; instead they had found each other through social connections and decided to live together. With bikes for transportation within their local community, a first aid kit, home grown crops and a pet, this family lives within a wider space, using basic infrastructures of the past such as water and solar power.

At first we situated this family away from the more built up, high rise metropolis, but then decided that it was more of a challenge – yet still more realistic- to situate Utopia as a part of this space. In order to actually survive and communicate, our family could not live away from others.

A focus on connectivity, not place, is what helped our thinking concerning the infrastructure of our utopia. Biohacking, co-presence facilitators, community management, homemaking and even a death café are vital to the creation and maintenance of the family’s utopia. Channels in and out of the space allow the community to be part of a wider network.

A focus on connectivity, not place, is what helped our thinking concerning the infrastructure of our utopia.

Trying to find current examples of how we change the environment we are in to benefit our wellbeing whilst thinking about the repurposing of space, we looked to the appropriation of parking spaces on Park(ing) Day. This is an annual worldwide event where artists, designers and citizens transform metered parking spots into temporary public parks.

When there are no more cars, what will we do with all the parking spaces?

The vision of Utopia may appear to be one that is merely in the future, yet the past and present provide examples of how small acts of utopia are mobilized.

This article has originally appeared on the blog of the Institute for Social Futures.

Georgia Newmarch is a PhD student at the Institute for Social Futures at Lancaster University, researching infrastructure and disruption. She tweets at @thenewmarch