Julia Gillen and her colleagues at the Edwardian Postcard Project are researching the early British postcards. She presents us her magnificent work on the proto-Instagrams.

I’m currently researching picture postcards of the format in use at the very beginning of the twentieth century in Great Britain. This was a time of extraordinary growth in mobilities of all kinds, including communication technologies and travel. Indeed the railways were at their zenith and people were enjoying innovations in communications revolution in some ways parallel to the social media phenomena of today.

For the first time people of virtually all sections of society had access to a cheap, attractive and extraordinarily fast communications technology, the picture postcard. There were several deliveries a day, for example six in central Manchester, and so at any time between 6am and 10pm a card could arrive. People sent and even received them almost wherever they were, keeping in constant touch with their nearest and dearest, or perhaps a very different category of people in their circles.

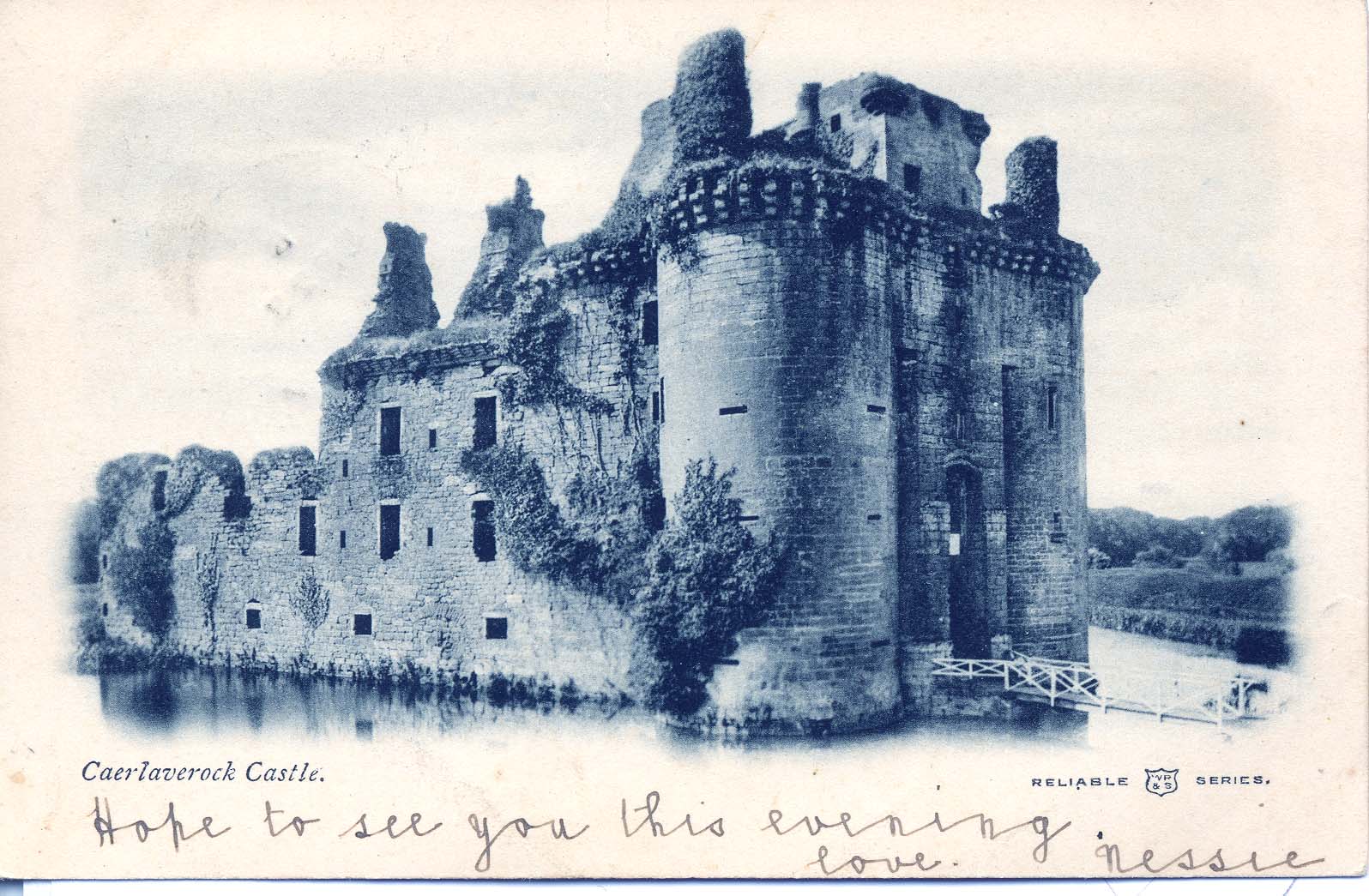

Between 1894 and 1902 one format of picture postcard was allowed: the whole of one side had to be used for the address. This, of course, also featured a stamp and postmark by the time it arrived, so locating its trajectory in time and space. The other side featured a combination of word and image. Although the three examples featuring here were all produced by postcard publishers (one French, imported into Great Britain) it was also possible to commission or create one’s own.

In the Edwardian Postcard Project, we’ve been transcribing and analysing the cards and also using public records, especially the censuses of 1901 and 1911, to research the people who used the cards.

Watch this YouTube video introducing the Edwardian postcard project

The Oxford card (top right) was sent by David Evans, an Oxford student, to his sister with whom he kept in virtually constant touch. His cards display a variety of images of Oxford, which sometimes relate to this movements there “Here is the street I walk along daily” he wrote on another, or, as here, tell her something about his current travels.

We have not been able to trace the sender or recipient of the “cute child” card, a then popular meme.

We have not been able to trace the sender or recipient of the “cute child” card (above), a then popular meme. The writer and recipient are living in a media-rich world; besides this card technology there is reference to the telegraph (only used by the relatively well-off in this era as unnecessary when cards travelled so quickly) and two popular magazines, the Strand and Pearsons. They are making arrangements to meet, plainly among the weight of other commitments; the writer’s promised “Titanic” efforts refer, of course, only to underlie the strength of his intentions rather than any unpredicted disaster ahead.

Finally, the card of “Caelaverock Castle” (above) illustrates with its extremely short message the speed as well as brevity made possible by these communications. It was sent and received within the town of Lockerbie, so the writer could know just how short a time it would take to arrive. The recipient was a Miss Janet Carmichael, aged 23, who lived in Buxton. Her father, a surgeon, who had died when she was under 3 had come from Scotland and Janet made quite frequent trips presumably to visit relations or other connections of his. Wherever she was, at home in Buxton or away, she kept up her postcard correspondence just as few of us give up communicating when travelling today.

The picture postcard of that era was extremely popular since it offered a release from the formality of the letter, which everyone had been taught to write at school, according to rules and conventions of the day. The postcard gave an opportunity to keep up rapid communications with people in your networks, allowed spontaneous writing and the sharing of an image that could be enjoyed by both. Although the restrictions on postcards were lifted in 1902, and a new divided back format permitted longer messages on half the address side, this format still remained popular over the next few years. ‘In ten years Europe will be buried beneath picture postcards,’ worried the Glasgow Evening News in October 1903.

‘In ten years Europe will be buried beneath picture postcards,’ worried the Glasgow Evening News in October 1903.

Of course there are differences between the picture postcard of the early twentieth century and any specific practice of today, whether Instagram, an SMS text message, Twitter, Selfie or other. But it is not simply a case of the postcard lacking affordances of today’s alternatives: how many platforms for example allow you to vary the size and appearance of your writing and have so much control of the layout?

The Edwardian postcard project has just received an AHRC Cultural Engagement Fund grant. We are planning to extend the participatory elements of the project in a citizen humanities direction. Please contact me if you would like to know anything further about the project.

Julia Gillen

Senior Lecturer in Digital Literacies and Director, Lancaster Literacy Research Centre.

Email: j.gillen[at]lancaster.ac.uk

Twitter: @juliagillen @EVIIpc