Elisa Mozzelin

I arrive in Lancaster from London after spending a few hours on the train, appreciating the landscape unfolding outside the window. It feels like those scenes in movies where actors remain still inside a moving vehicle, while a rolling landscape is projected in the background to give the illusion of travel. However, it is me who is moving, though stationary, inside the train carriage along with people getting on and off.

Since I have read it, every time I board a train, I think of Schivelbusch’s The Railway Journey (1977) where he talks about Panoramic Travel and how the passenger is “shot like a bullet through the landscape” that it is transformed into geographical space by the phenomenon of industrialization of both space and time. Although the smells and sounds of the outside landscape are muted by the coach – an enveloped experience – I hear passengers talking (in dialects I cannot decipher), I smell sandwiches, and I feel the air conditioning blasting from under the seat. My perception of the landscape is not denied; it does not become merely “geographical” (without GPS, I wouldn’t even know where we are); instead, it layers to the one I am experiencing inside the cabin.

In this context, the biographical and subjective component is enhanced because, while observing, I ask myself: what would those fields smell like and what sound would the trampling of that grass make? The many visual information I receive from the landscape amplifies my imaginative experience rather than reducing it. Although I cannot touch that grass, I can try to imagine its texture. In the meanwhile, someone chats in the corridor, my legs are still, and I chew some packed lunch. It is as if my experience were a double photographic exposure, in which the elements in the shot overlap.

Outside the window, I observe a landscape I’m not used to: practically flat hills, green grass, vast fields populated by sheep and cows. It reminds me of that Pink Floyd album’s cover, is it Atom Heart Mother? It’s very different from the mountainous, hilly, or Palladian landscapes I’m accustomed to when traveling by train in the region I come from. “There it is!” I think, “the famous bushes on which Karl Marx based his theory of primitive accumulation.” Here, they take on the appearance of true iconemes (as Eugenio Turri would define them), recognizable forms that distinguish a specific landscape, but I’ve never seen them before in my country.

Arrived in Preston, it’s time to get off and reboard the locomotive with my large bags and bulky backpack that slow me down and probably make me look clumsy. Here, with me, several people get on the train, dressed in technical jackets, backpacks, hiking boots, and walking sticks: they are ready to hike. Some time later, I understand that they were probably heading to the Lake District. Some passengers argue about assigned seats, but some other insist that in the end, it doesn’t matter where you sit; the important thing is to have a ticket and enjoy the journey.

45°54’21″N 11°54’18″E

I came to Lancaster because my doctoral research in Political Philosophy focuses on walking, or rather, because I try to detect the political component of this mobility practice. I am interested in studying the relationship the body entertains with social space (see: Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 1974). Actually, this issue is much more complex, especially if we claim a feminist approach. Indeed, even talking about “space” and “body” as if they were universal entities is problematic, and in my doctoral journey, I am trying to write from this awareness. For this reason, I am interested in the political-biographical component of subjects in motion and in the politics of mobility that derives from a politics of location based on social relationships.

Coming to the Center for Mobilities Studies of Lancaster University was quite a thing for me because this institution, along with being a leading one in the field of Mobilities Studies, represents an historical benchmark for these topics.

From this experience, I gained more than I expected in terms of academic research. The time I spent there has allowed me to delve deeper into the political perspectives on mobilities. In this regard, I have tried to research not only how walking can have political consequences (how walking can actively transform urban spaces), but also how it can be considered a social product itself. It was interesting to delve into the relationship between mobility and politics, contextualize the new mobilities paradigm, the theme of mobility justice and write about power geometry and the inseparable link between mobility and space, which is fundamental for me as I come from a Lefebvrian tradition of thought on social space.

The time spent at CeMoRe has been particularly valuable for reflecting on the politics involved in mobility relations from a transdisciplinary and interdisciplinary perspective. Thanks to productive discussions with my supervisor prof. Lynne Pearce, to whom I am particularly grateful, and other scholars (particularly prof. Colin Pooley, prof. Jen Southern, and PhD Aleksandra Ianchenko) I have been able to reconstruct an overview of the contribution Mobilities Studies has brought on a Political transdisciplinary and multifaceted perspective.

To Lancaster, I am particularly thankful for the long walks that took me from the campus to the surrounding area, from the city center with its canal, to the mouth of the River Lune in Glasson Docks and the wetlands of Morecambe.

Morecambe Bay (Olympus Mju ii, Kodak Pro Image 100)

53°59’53″N 2°51’11″W

It’s Sunday, and it’s a beautiful sunny day. The sky in Lancaster seems wider, perhaps because I’m used to the mountains and five-story buildings that crown the places where I walk. I lived for years in Venice, and from the narrow, confined space of the “calli”, the sky looked like a flowing stream.

From the Graduate College, I walk to Ellel and then Galgate. It’s interesting to note how, despite being immersed in the countryside, just a few kilometers away runs one of the longest highways in England, the M6.

Car in Ellel (Olympus Mju ii, Kodak Pro Image 100)

From a distance, I can hear the hum of passing cars. As I stroll, some windows between the bushes offer glimpses of the traffic heading north toward Scotland. Even from the Ellel cemetery, a space surrounded by flourishing greenery (where I always find a cat perched on the wall), you can see the colorful trucks speeding down the road in the distance.

I pass the Silk Mill and cross a narrower road lined with terraced houses. I stop at a SPAR, buy some cookies, which I eat along the road that runs alongside the railway tracks. It is curious to think how this tiny stretch of land I am crossing separates two of England’s most important thoroughfares. Yet, this space is seemingly motionless, still. Time seems to collapse into space, as if nullified: I walk while eating biscuits, the windows sills of the terraced houses in Chapel St. are decorated with strange knick-knacks (one lady displays a sign saying ‘Fresh Eggs’), the cat is perched on the brick wall.

I take the road that runs alongside the river [Conder]: we are in the middle of the countryside. I meet a cyclist, a mother with her son. The boy seems happy; I can tell by the fact that his smile is flashes under his beige cap while he walks and points at the cows behind the gate between the hedges.

Cows approaching in Galgate (Olympus Mju ii, Kodak Pro Image 100)

I walk into the landscape, following the course of the river. Here, I don’t meet anyone: just some brick bridges in which there is a strong echo and strange dams [later Prof. Southern will explain that they were used to pull the boats up in the sections where the water was lower]. All I hear is the sound of the river and the rustling of ears of corn in the wind. The river divides the space in two: on one side are the grazing sheep and cows, on the other are the high-voltage pylons sequence that stand perfectly aligned like fierce monuments, as if they had always been there.

Sheep at pasture (Olympus Mju ii, Kodak Pro Image 100)

I move forward: with my analog camera, I try to capture these phenomena and freeze them on photographic film. I walk and shoot, then I take a sit and eat a couple of biscuits whose box (I now notice) states: product of Germany. In the meanwhile, the sheep graze under the trees, electric power flows through the high-voltage wires, the river runs towards the estuary. Probably, few kilometers away, some train is transporting someone towards Glasgow.

Sheeps on a backdrop of sky (Olympus Mju ii, Kodak Pro Image 100)

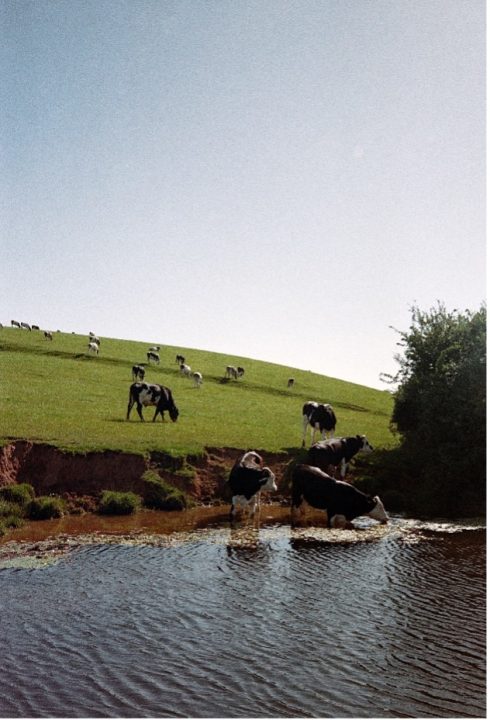

I continue my walk towards the estuary, and for at least another half hour, I don’t see anyone. I approach a bridge over which a lightly trafficked road seems to pass. I continue along the river, and soon I pass by a farm and what I believe is a holiday village that’s still closed. Some cows are cheerfully bathing in the water.

Cows chilling in the River Conder (Olympus Mju ii, Kodak Pro Image 100)

The landscape starts to change and becomes more populated as the river opens into a sort of small harbor. I believe I’ve arrived at Glasson Docks; it’s around 5 PM. As a yellow high-visibility vest flutters, indicating some ongoing work, I sit on a stone wall in front of some terraced houses. Someone nearby parks, probably returning home after a day visiting relatives. I wait for the bus.