Melissa Jayne Ball

The ambition of Public Health England is for all children to avoid tooth decay as they grow, yet this issue remains the most common reason for which young children are hospitalised. Negligence surrounding this subject was acknowledged by the government ten years ago and plans were introduced to improve statistics. However, studies have shown that although improvements were seen between 2012 and 2017, present statistics show improvements to have reached a standstill (PHE, 2020, p.5). If improving oral health was a governmental priority, one may question why progresses have come to a halt. It is the opinion of many that more must be done to promote good oral health, which includes educating parents and supporting those who work with children. This is particularly important as almost all cases of dental cavities in children are preventable (Institution of Health Visiting, 2015; PHE, 2019). The participants to be involved in this research consists of dental professionals and parents of early years/school aged children. Using the methodology of the questionnaire, parental awareness of strategies and knowledge upon the promotion of oral health will be determined. Furthermore, interviews will be conducted with dental professionals to discover whether they feel parents are well informed upon such strategies.

Melissa Jayne Ball

The ability to communicate and eat without distress, embarrassment and disease is all dependent on the standard of oral health, which is a vital aspect of general health and wellbeing. Poor oral health in children has been a public health concern for some time, particularly as they are more likely to suffer from tooth decay than adults. Previous developments had been observed but have recently come to a halt, which suggests that more must be done to tackle the issue.

Did you know?

The most common reason for admission into hospital for five to nine-year-olds is tooth extraction.

Almost all oral health issues in children are preventable by implementing a good oral health routine.

Various literatures have shown parental influence to be of high significance regarding the oral health of their children, yet questions may be raised as to whether parents are offered adequate support and information. This research aims to analyse the importance of oral health within children and current strategies promoting this, alongside any barriers or inequalities which may arise.

Many implications are associated with oral health issues, such as pain, communication problems, inability to eat, and embarrassment. All these factors contribute to a child being unable to develop and thrive in a way that they should. Other health and social care issues are also linked with poor oral health, such as obesity, malnutrition and in some cases, safeguarding concerns. Parents also reported feeling stress, anxiety, and guilt. Furthermore, parents must take absence from employment and children lose days at school due to dental appointments and related hospital admissions.

The Figures

A survey conducted in 2019 found that 23.4 percent of children had experienced tooth decay by the time they reached five years old.

There are over eight thousand children under five requiring tooth extraction per year, with the annual cost of this procedure across all children costing around fifty million pounds.

There has been an increase of almost a quarter in this past decade.

Within the Statutory Framework for the Early Years Foundation Stage, it states that practitioners must promote the good oral health of all children. Practitioners should try to identify children in their care who have poor oral health and collaborate with parents and other professionals to offer support.

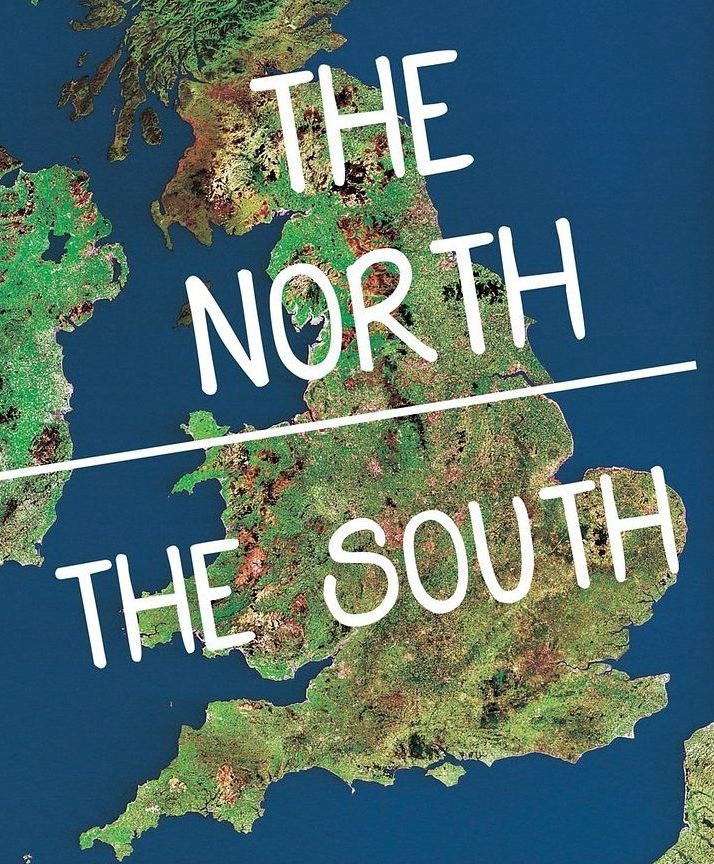

The North-South

Divide

Studies established that 34.3 percent of children living in the North West had experienced dental cavities compared to 13.7 percent who lived in the South East.

Those living in the North West also proved less likely to seek medical help for dental issues than those living elsewhere in the UK.

A main reason for dental cavities is the consumption of sugar, as this contains acids which damage teeth.

In 2015, all businesses in the food industry were asked to reduce the sugar in their products by twenty percent by 2020. Unfortunately, little changes have been observed, therefore further strategies must be implemented to make these changes.

Public Heath England suggest that oral health is included in all discussions surrounding healthy eating within schools and early years settings, to aid the prevention of dental decay.

As part of their Change4Life initiative, the NHS provides a wealth of information to parents and children regarding health eating. This includes ways to decrease the amount of sugar consumed and how to choose healthier alternatives. However useful this information may be, it does not change the fact that healthy food is often more expensive than a less healthy alternative. Therefore, those families living in deprived areas may face a predicament.

A role of the health visitor includes supporting and advising parents as to when and how to begin a toothbrushing routine, alongside dietary information to keep teeth healthy. These conversations should be had in the first weeks of the child’s life and continue within checks throughout their childhood. An issue to be considered however, is a lack of evidence upon whether these conversations prove effective.

A role of the early years practitioner is to discuss the importance of health eating and toothbrushing, with some settings qualifying for a toothbrushing programme. Within the programme, practitioners will receive training from outside professionals, who will also offer support to parents. Not only will the focus be upon daily brushing within in the setting, but also regularly brushing at home. Many believe that the routine behaviour of toothbrushing is most effectively taught by parents. Aiding parents to establish a regular toothbrushing routine in the hope it becomes a habit has been described as highly important. Not only will this benefit the child, but also influence their oral health as they become adults.

Absence of parental involvement with oral health promotion was believed by adolescents a reason for tooth decay. This corresponds with the claim that the oral health of the child is greatly influenced by parental attitude, knowledge, and their own oral health status. Furthermore, many parents do not realise the importance of good oral health.

As the child grows, parents are also crucial in relation to reinforcing the advice given by the dentist whilst at home. It has been suggested that parents are key players in the enabling of interaction between the dentist and child during consultations. It is not only important to educate the child regarding the importance of good oral health, but also to educate the parent, for it is this knowledge that will also impact the life of the child.

Although recommendations have been made to ensure the availability of dental services, the current pandemic has caused complications in this matter. This has been an ongoing issue, with covid only heightening the problem. In 2016, a survey revealed a fifth of participants struggled to arrange a dentist appointment within an acceptable timeframe. This figure has risen significantly, with recent surveys showing seventy-five percent of participants found accessing dental appointments challenging. Delays caused by lockdown have also resulted in children requiring preventable tooth extractions. In recent months as restrictions have been lifted, it is still proving difficult to visit a dentist for a routine check up as urgent cases have taken priority. Some have reported having to wait up to three years for appointments, whilst those who are not contacting the dentist at all are being withdrawn from their services.

Conclusion

From the information presented, it can be concluded that poor oral health within children remains a significant public health issue, particularly within areas of deprivation. The English government must make oral health a priority within future policies, so that strategies may be implemented to improve the oral health of its nation and narrow the gap of inequality. There is no doubt that prevention is better than cure in relation to tooth decay, therefore early intervention is essential for statistics to improve. It can be widely argued that parental influence is key to promoting the oral health of children, however it appears an unimportant subject to many. Greater information must be provided to both parents and children to break the cycle of generational trends and improve the oral health of the nation.

References

Agel, M., Marcenes, W., Stansfeld, S.A. and Bernabé, E., (2014) ‘School bullying and traumatic dental injuries in East London adolescents’, British dental journal, 217(12), pp. 1-5. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/sj.bdj.2014.1123.pdf?origin=ppub (Accessed 12 January 2022).

Aunger, R. (2007) ‘Toothbrushing as routine behaviour’, International Dental Journal, 57(0), pp. 1-13. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/3007929/Tooth_brushing_as_routine_behaviour (Accessed 14 January 2022).

Department for Education (2020) Development Matters: Non-statutory curriculum guidance for the early years foundation stage. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/development-matters--2 (Accessed 21 December 2021).

Fuller, G. (2017) ‘How to prevent tooth decay’, Childcare Professional, (Summer), pp. 32-36.

Hall-Scullin, E., Goldthorpe, J., Milsom, K. and Tickle, M. (2015) ‘A qualitative study of the views of adolescents on their caries risk and prevention behaviours’, BMC Oral Health, 12(141), pp. 1-10. Available at: https://bmcoralhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12903-015-0128-1 (Accessed 15 January 2022).

Institute of Health Visiting (2015) Looking after your children’s teeth. Available at: https://ihv.org.uk/for-health-visitors/resources-for-members/resource/ihv-tips-for-parents/health-wellbeing-and-development-of-the-child/childrens-teeth/ (Accessed 21 November 2021).

Local Government Association (2019) A whole systems approach to tackling childhood tooth decay. Available at: https://www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/15.70%20Whole%20systems%20approach%20to%20tackling%20childhood%20tooth%20decay_03_1%20WEB.pdf (Accessed 23 November 2021).

Public Health England (2020) National Dental Epidemiology Programme for England: oral health survey of 5-year-olds 2019. A report on the variations in prevalence and severity of dental decay. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/oral-health-survey-of-5-year-old-children-2019 (Accessed 28 October 2021).

Stevens, C. (2017) ‘I’ve had to remove all of a toddler’s teeth. It’s time for a war on sugar’, The Guardian, 10 April. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/healthcare-network/views-from-the-nhs-frontline/2017/apr/10/surge-dental-surgery-children-nhs-consultant-dentistry (Accessed 16 January 2022).

Slide 1 image (max 2mb)

Slide 1 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 1 Caption

Slide 2 image (max 2mb)

Slide 2 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 2 Caption

Slide 3 image (max 2mb)

Slide 3 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 3 Caption

Slide 4 image (max 2mb)

Slide 4 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 4 Caption

Slide 5 image (max 2mb)

Slide 5 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 5 Caption

Slide 6 image (max 2mb)

Slide 6 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 6 Caption

Slide 7 image (max 2mb)

Slide 7 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 7 Caption

Slide 8 image (max 2mb)

Slide 8 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 8 Caption

Slide 9 image (max 2mb)

Slide 9 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 9 Caption

Slide 10 image (max 2mb)

Slide 20 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 10 Caption

Caption font

Text

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)