Ella Stanley

Contrary to the popular belief that those who engage in project politics are ‘sucking up, scheming, and manipulating (McIntyre, 2003, p.3), the positive function of politicking began to be highlighted within twentieth-century academic literature by the likes of Yourker (1991) and Pinto (1998). A framework was developed to aid project managers navigate organisational politics to create and maintain power within project teams. Because a project manager traditionally lacked status and authority, influence became the key driving force. However, few investigations have since been conducted. In this research gap, project management has increased its formal standing as a profession via chartership and certification (Blomquist, Farashah and Thomas, 2018). Therefore, the research question presents itself: is the framework from over two decades ago still topical, or is there now a better way to ‘play the game’? The methodology for this research is using a sample of practising project managers conducting semi-structured interviews to collect qualitative data. Whilst research is ongoing, preliminary findings suggest the answer is dependent on who the target is. The anticipated implication of this research is to develop a modified guide for project managers on how to positively engage in organisational politicking to their advantage; ultimately resulting in an increased chance of project success.

Ella Stanley

Project Politics - How to Play the Game in the 21st Century

A project manager may engage in political behaviour by adopting any process by which they ‘seek to acquire and maintain power’ (Pinto, 1998, p. 85) over the project team and / or the stakeholders they wish to govern. Yourker defines the concept of power as ‘the ability to get others to do the work (or actions) you want regardless of their desires’ (1991, p. 36).

Whilst traditionally political behavior is viewed negatively with participants ‘sucking up, scheming and manipulating’, the positive politicking function of ‘building relationships, developing strategies and opening communication channels’ (McIntyre, 2003, p.3) is becoming more widely recognised. Cases studies – such as Warne and Hart’s (1996) investigation into Information Systems project failure – highlight that even when most of the traditional success factors are present, failing to recognise and actively manage ubiquitous politics within a project has the potential to significantly increase the threat to the success.

Most research into this topic was conducted in the 1990’s by the likes of Pinto (1998). This leading academic in the field endorsed the notion that because project managers have minimal status or authority, they must rely exclusively on influence to successfully participate in project politics. However, in the two decades spanning this research gap, the discipline has gained momentum as a respected function through the likes of the Association for Project Management and Project Management Institute. Consequently, the ability to receive chartership and formal project management certification now provides project managers with status and leverage to gain authority in management positions (Blomquist, Farashah and Thomas, 2018). Therefore, is there now a better way to ‘play the game’ than simply relying on influence?

Methodology

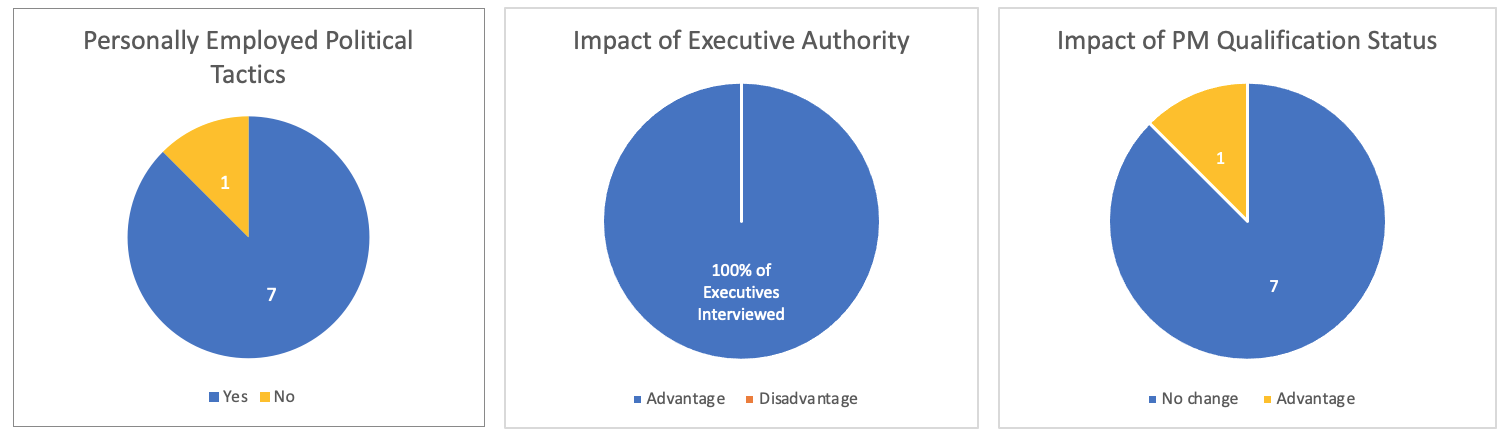

Initial research suggests that in the research gap, there are now new techniques project managers may utilise beyond influence to acquire and maintain power within a project. Specifically, the visibility of authority the individual possesses appears to offer an advantage when engaging with organisational politics. Therefore, an updated framework may be proposed of how to best ‘play the game’ in the 21st century to improve upon a project manager’s politicking ability; ultimately increasing the likelihood of project success.

A special thank you to Andy Smith for his support and guidance throughout my degree and research project. Additionally, I’d like to thank those who gave up their time to be interviewed and contributed to my investigation.