Carrie Lee

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, single-use plastic (SUP) has become paramount to healthcare staff and the public, resulting in excess waste. Each COVID-19 test is around 10g of plastic. Consequently, if every child and adult in the UK tested twice a week, this would amount to more than 1000 tonnes of plastic waste per week, in turn, filling an Olympic size swimming pool in less than a month (Dunn, 2021). With a ‘throw-away culture’ among society and no alternatives to SUP, ecological health is facing an inevitable decline.

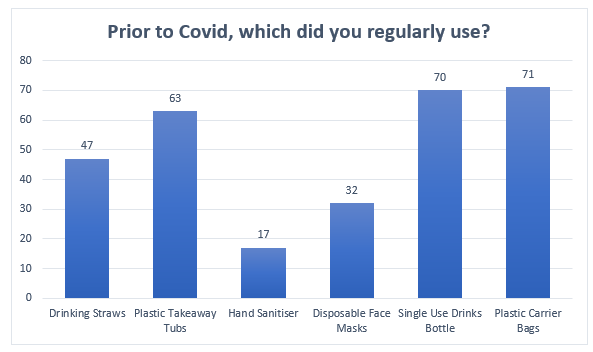

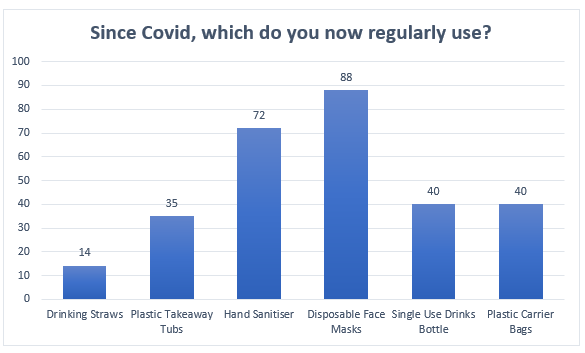

This research provides a critical review of plastic usage throughout the pandemic while obtaining public attitudes on their use and understanding of the impact, furthermore, determining the relationship between ecological and human health. The findings concluded a change in the items consumed throughout the pandemic. However, the items commonly used are still SUP, this reaffirming that the dominant perception of plastic is the role of a protector rather than a polluter (Parashar and Hait, 2020).

Carrie Lee

This research sought to explore public behaviour towards single-use plastics throughout the pandemic. The intention was to obtain an understanding of the environmental impact of the pandemic.

Prior to COVID-19, single-use plastics (SUP) were predominantly seen as a polluter, but as a result of COVID-19, their primary role became a protector, resulting in less attention on the environmental impact.

In healthcare industries, single-use plastics such as masks, visors, gloves, and aprons became paramount in keeping the key workers safe. Also, masks also became mandated for public use.

Many products in daily life were restructured for reducing covid transmission and extending shelf life. This saw a further surge of plastic, and the steps which had been made (i.e bamboo cutlery, bags for life, less food packaging), were reverted back to plastic.

Plastic waste is often sent to landfills, for incineration, or burial, all of which are problematic to the environment. From releasing greenhouse gases to stray plastic reaching open waters where they break down into microplastics (<5mm). Both marine life and human health become at risk of contamination through these microplastics.

Methodology

To conduct this primary research, a questionnaire was distributed on social media, seeking a random sample of participants to give a broader range of demographics.

Using both open-ended and closed questions, I was able to obtain a triangulation of quantitative and qualitative data which would assist in a better understanding of how plastic usage had changed since the pandemic.

This research has undergone ethical clearance and all data collected was in accordance to GDPR and B&FC regulations.

How long do these plastic items take to degrade? Have a guess then click on the images to find out

(underneath if mobile view)

20 years

450

years

500 years

200 years

10 years

Findings

Over 50% of participants were aged between 18-34 years old.

84.7% of which were female.

Of the 111 participants, 23 of which worked in the healthcare industry, the additional 88 participants were of varied occupations.

62.2% of participants claimed they have heard LESS news and media reports on plastic pollution throughout the pandemic.

87.4% of participants said they feel they are able to make changes to tackle plastic pollution. 3.6% oppose this, and 9% felt neutral.

Conclusion

This research conducted a critical analysis of the use of plastic throughout the pandemic. Due to COVID-19, PPE inevitably became life-saving protection, however, the findings indicate there has been a shift in the plastics which are used. This suggests the perception that plastic has become a protector rather than a polluter has created an ideology that sustainability in healthcare is not a priority. Furthermore, the lack of recycling facilities resulted in a magnitude of plastic waste, often disposed of incorrectly, much of which ends up incinerated, landfill, or buried - all of which are problematic to the environment.

91% of plastics do not end up recycled, and of those which do, they can often only be recycled a couple of times, therefore, the ideology of sustainable plastic is often disillusioning. Most plastics are non-degradable meaning they do not compose but instead break down, and as seen above, this is over a long period. Throughout this, microplastics are created, posing risks to both marine life and human health through inhalation or contaminated foods (seafood, vegetables, fruit). Despite the awareness of the harms surrounding plastic, the 'throwaway culture which has been created throughout the pandemic presented an ideology that the transmission risk reduced. Yet, it has to be argued that a re-usable shopping bag could not pose any further transmission risk than that of one's shoes or clothing.

While some changes have already been made as the pandemic has eased, it is important that we do not lose sight of the harms created by plastic and continue to challenge whether it is essential. It is an individualistic responsibility to do what we can to ensure lesser plastic is used, in turn, less plastic waste is created.

Fruit and vegetables do not grow in plastic, so why do we persist to cover them?

References

Burki, T. (2020). Global shortage of personal protective equipment. The Lancet. Infectious diseases, 20(7). P.p. 785–786. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30501-6> [Accessed 19 February 2021]

Dunn, C. (2021). 'Covid has made us use even more plastic - but we can reset'. [The Guardian]. 19 July. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/jul/19/covid-plastic-lockdown-resource (Accessed 7 January 2022)

Parashar, N., & Hait, S. (2021). Plastics in the time of COVID-19 pandemic: Protector or polluter? The Science of the total environment, 759, 144274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144274

Wyatt, T. (2020). Gendering Green Criminology [webinar]. Available at: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/gendering-green-criminology-tickets-124094003505

WHO - World Health Organization. (2020). Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and considerations during severe shortages. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/rational-use-of-personal-protective-equipment-for-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-and-considerations-during-severe-shortages [Accessed 27 January 2021]

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Rachael Leitch (Conference supervisor), David Hayes (Research Supervisor), and Fatema Desai (Programme Leader) for all the words of encouragement and support over the last few years.

Contact

For more information about this study, feel free to contact me.

Email: 30041318@blackpool.ac.uk

Twitter @CarrieLee_121

Slide 1 image (max 2mb)

Slide 1 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 1 Caption

Slide 2 image (max 2mb)

Slide 2 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 2 Caption

Slide 3 image (max 2mb)

Slide 3 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 3 Caption

Slide 4 image (max 2mb)

Slide 4 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 4 Caption

Slide 5 image (max 2mb)

Slide 5 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 5 Caption

Slide 6 image (max 2mb)

Slide 6 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 6 Caption

Slide 7 image (max 2mb)

Slide 7 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 7 Caption

Slide 8 image (max 2mb)

Slide 8 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 8 Caption

Slide 9 image (max 2mb)

Slide 9 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 9 Caption

Slide 10 image (max 2mb)

Slide 20 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 10 Caption

Caption font

Text

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)