Adam Stanney

The existing historiography on the maritime societies of the early medieval North Sea centres primarily on the cultural and economic links between coastal settlements, as well as the social constitution and power hierarchies of these economies. Though a dynamic field of research, these studies have often grounded themselves in singular debates, such as the question of economic agency in a particular place, or the cultural diffusion in one geographic area. While much scholarship, modern in particular, does highlight the distinct interconnectivity of the North Sea basin and does discuss character of settlements themselves, these are rarely tackled in tandem, and a cohesive characterisation of the pre-Viking North Sea world is thus distinctly lacking. My research seeks to amend this by taking three major North Sea emporia – Ipswich, Dorestad, Ribe – as case studies. Dynamics within the settlements themselves, between the settlements and their hinterlands, and between the emporia themselves will be analysed together. Placing itself within modern thematic discourse on urbanism and networks, as well as straddling the boundaries of various disciplines and research foci on emporia, a holistic characterisation of the North Sea world will be the primary aim of the research.

Adam Stanney

W E L C O M E T O M Y P R E S E N T A T I O N W E B P A G E , which will summarise my dissertation research into the early medieval North Sea. This research takes three trading communities – or emporia – as case studies; Ipswich in East Anglia, Dorestad in the Netherlands and Ribe in western Denmark.

The aim of this research is to paint a holistic image of the pre-Viking world, analysing these case studies with respect to key three areas; the economic and social interconnectivity between emporia, the socio-economic trends within them, and how they fit into wider trends of medieval urbanism.

Each section below will discuss a chapter of the dissertation, before bringing them together and indicating opportunities for further research.

A map of major emporia, with the dissertation's case studies in red

I N T E R C O N N E C T E D W O R L D

It is the Vikings who are, in the public consciousness, associated most heavily with long-distance trade and communication. However, maritime activity was incredibly advanced in the years before the Viking Age. The diffusion of cultural norms as well as economic activity can be seen below, and an argument for deep cultural and economic connectivity is laid out on this basis in the first chapter. Here we can see a truly interconnected North Sea world.

Some evidence from England

Cultural – English missionaries such as Willibrord travelled to the Continent to places such as Utrecht, near the key case study of Dorestad, spreading religious ideas.

Economic – aside from the plethora of international material found at Ipswich and its satellite sites, coin loss at comparable emporia such as Hamwic (Southampton) indicates heightened trade. Parallel sites are useful in the study of this research area and the early medieval period more broadly, as evidence may be scant in some areas.

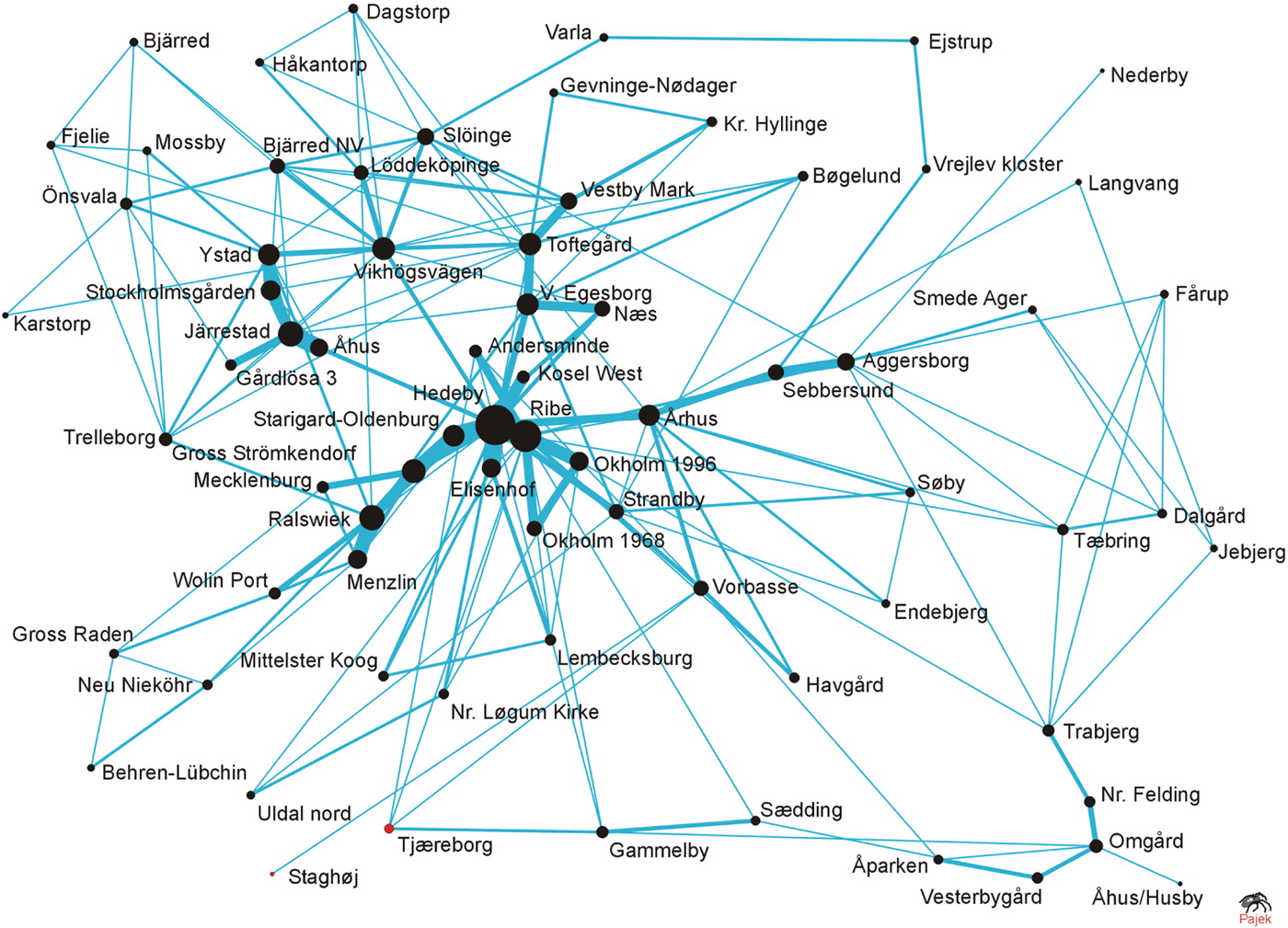

Søren Sindbæk’s network model – emporia are conceptualised as nodes within a network. The degree of cultural and economic connection between sites is proportional to the proximity it has to a major node. Thus, hinterland settlements or smaller trading sites will exhibit more markers of international connection if they are in close communication with emporia.

The Dorestad Sword, an example of a high-status trade good

An early-modern engraving of St. Willibrord from the Netherlands

K I N G S A T T H E C O A S T

Running through most major scholarship on the pre-Viking economy of the region is the extent to which royal agents were involved in the inception, proliferation and development of emporia, and by extension the extent to which kings commanded the networks laid out in the previous chapter. Although it is an incredibly nuanced historiographical debate with a spectrum of opinion, its two main camps are exemplified by work of two scholars, Richard Hodges and Christopher Loveluck, whose arguments are discussed below. The second chapter settles on the Loveluckian end of the spectrum, but not without some qualification. Namely, that there is certainly room for royal agency, yet this varies from place to place and was often of an opportunistic nature, taxing and controlling trade after the fact. In essence, kings came to the coast.

Totemic pieces of scholarship

Richard Hodges – primarily presented in Dark Age Economics (1982), Hodges assigns agency to the royal party. Emporia are conceptualised as trading settlements that foremost serve elite goods exchange, with these high-status products fuelling a king’s patronage network. Thus, little agency is left for any but the upper echelons of society.

Christopher Loveluck – representing more modern trends in historiography, Loveluck argues strongly against Hodges’ ideas and highlights the contributions of the merchant class to the formation of emporia and subsequent North Sea network. Trade instead served the needs of communities, which pursued disparate and sporadic trade according to self-interest. Thus, Hodges’ thesis is flipped on its head, with most agency being assigned to individual merchants and maritime communities rather than national elites.

Dagfinn Skre – an example of a halfway house within the debate, Skre acknowledges the contributions of both sides and incorporates them into a holistic characterisation. For instance, royal involvement can certainly be recognised in the form of infrastructure and protection, yet this formalised and transnational framework allowed merchants to pursue a profit incentive as opposed to a form of trade strictly monitored by local social norms. Thus, Skre harmonises elements of this debate and creates space for elite and non-elite agency.

Primary material in relation to royal control

Numismatic evidence – coins finds could indicate a royal framework within which trade is conducted, depending on things such as the design of the coin.

Urban planning – postholes and plots could indicate widescale, unfirm organisation by a king. However, this should not be taken ipso facto as royal agency, as local elites – or even merchants themselves – could have been capable of urban organisation on some scale.

Literary sources – tax edicts could indicate the nature of royal control over a particular emporia or trade route. Furthermore, a chronicler’s mention of merchants could indicate a cultural inclination to associate an ethnic or social group, or geographical area with travel and trade.

An example of royal coinage - a Middle Saxon penny from East Anglia - which may indicate a royal framework for trade

A visualsation of network theory using settlements in Denmark

The above diagram laid onto a geographical map. The extent of connections with Ribe can be seen here, as well as places such as Hedeby

A S T E P P I N G S T O N E T O T H E M O D E R N ?

Considering the portrayal of emporia as vibrant, international and wealthy centres, it may be tempting to see them as the early medieval equivalent of our modern cities. While there is an element of truth to this, a closer inspection of just how urban these centres were, as well as the variety of their function, reveals a more nuanced image. These settlements can doubtlessly be fitted into wider trends in pre-modern urbanism, yet they were unique settlements and should not be viewed teleologically – that is, seeing emporia solely as a stepping stone to modern urbanism as opposed to phenomena in their own right.

Some select qualifications utilised to explore urbanism

Permanency? – whether a settlement is inhabited all year round or not is a key marker of urbanism. In the case of Ribe, scholarship was previously settled on this emporium being a seasonal settlement. However, the application of evidence from archaeological digs at places such as Sct Niclojgade 8 has brought this into question. Croix has argued in favour of several markers of permanency at Ribe, such as the levelling and stabilising of land as well as previously unknown permanent buildings. The permanency – and thus urbanism – of emporia can now be affirmed.

One dimensional function? – there is limited evidence that there was a political dimension to emporia. The fact that these were economic mines for kings, as opposed to seats of administration, forces us to reconsider their place in a linear development towards the towns of the later Middle Ages, despite clear aspects of urbanism such as permanency. As Moreland puts it, “we destroy the distinctiveness of economic processes in the eighth century by the imposition of evolutionary and developmental models”.

An artist's impression of daily activity at early medieval Ribe

A comb found at Ribe - an example of everyday items common at emporium sites

T H E N O R T H S E A W O R L D

Drawing these conclusions together, a general image emerges. Fundamentally, the pre-Viking North Sea was:

- An area with not only a sophisticated regional economy, but also a shared maritime culture.

- Created and developed by all strata of society, not just kings.

- Important to the development of northern European urbanism, but a crucially unique phenomenon.

The maritime peoples of the post-Roman era, serving their own needs, communicated in a variety of ways, with emporia as te vehicles of this, and subsequently developed complex networks that proved formative to the later history of the North Sea world and beyond.

Further avenues for research?

- Utilising more fully emporia that have been used here only in a comparative/secondary manner, such as Eorfowic (York), Quentovic, Hedeby, could either strengthen or alter the conclusion of the dissertation.

- Incorporating Channel, Baltic and Arctic trade, which often overlapped with that of the North Sea, could enrich the understanding of networks and test the models applied in this dissertation.

- Continuing the story into the Viking Age could be useful for more focussed research into the later development of northern European towns.

B I B L I O G R A P H Y :

Croix, Sarah, ‘Permanency in Early Medieval Emporia: Reassessing Ribe’, European Journal of Archaeology, 18.3 (2015), 497-523

Higham, Nicholas J. and Ryan, Martin J., The Anglo-Saxon World (United Kingdom: Yale University Press, 2015)

Hodges, Richard, Dark Age Economics: the Origins of Towns and Trade A.D. 600-1000 (London: Duckworth, 1982)

Loveluck, Christopher, Northwest Europe in the Early Middle Ages, c.AD600-1150: A Comparative Archaeology (New York: United States of America: Cambridge University Press, New York, 2013)

Skre, Dagfinn, ‘Towns and markets, kings and central places in south-western Scandinavia c. AD800-950’, in Kaupang in Skiringssal, ed. by Dagfinn Skre (Denmark: Aarhus University Press, 2007)

Skre, Dagfinn, ‘Post-substantivist production and trade. Specialized sites for trade and craft production in Scandinavia c. 600-1000AD’, in Maritime Societies of the Viking and Medieval World, ed. by James H. Barrett and Sarah Jane Gibbon (United Kingdom: Maney Publishing, 2015)

Sindbæk, Søren M., ‘Networks and nodal points: the emergence of towns in early Viking Age Scandinavia’, Antiquity, 81.311 (March 2007), 119-132

Sindbæk, Søren M., ‘The Small World of the Vikings: Networks in Early Medieval Communication and Exchange’, Norwegian Archaeological Review, 40.1 (2007), 59-74

Slide 1 image (max 2mb)

Slide 1 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 1 Caption

Slide 2 image (max 2mb)

Slide 2 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 2 Caption

Slide 3 image (max 2mb)

Slide 3 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 3 Caption

Slide 4 image (max 2mb)

Slide 4 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 4 Caption

Slide 5 image (max 2mb)

Slide 5 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 5 Caption

Slide 6 image (max 2mb)

Slide 6 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 6 Caption

Slide 7 image (max 2mb)

Slide 7 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 7 Caption

Slide 8 image (max 2mb)

Slide 8 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 8 Caption

Slide 9 image (max 2mb)

Slide 9 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 9 Caption

Slide 10 image (max 2mb)

Slide 20 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 10 Caption

Caption font

Text

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)