Phoebe Kendrew

Scholars have often explored the array of exchanges that occurred with the discovery and colonisation of the New World. The transfer of diseases was a destructive repercussion of this process, particularly for the indigenous populations. Amongst the Aztecs, a term to describe one disease was cocoliztli, which is yet to be explicitly defined. Epidemics re-emerged throughout the sixteenth century, with two particularly devastating episodes occurring in 1545-8 and 1576-80. The Relaciones Geográficas, completed between 1577-85, is a rich source for colonial and indigenous life in its own right and is yet to be explored in relation to cocoliztli. Difficulties in analysing the corpora have been overcome through the use of digital humanities, a rapidly developing field. By employing text mining techniques, close analysis of large corpora is increasingly feasible. My research will examine the portrayal of cocoliztli within the Relaciones Geográficas in relation to Nahua ideas of disease and health. It will consider how the disease was addressed, while consolidating upon pre-existing knowledge of the cause and cures of disease. It will provide further evidence of the prevalence of indigenous ideas, as part of an ongoing discussion of decolonisation to reclaim cultures and highlight marginalised voices.

Phoebe Kendrew

Introduction

With the colonisation of the Americas, the 'New World', numerous exchanges took place. One example is the biological exchange through the spread of diseases. Indeed, the Spanish conquest of Mexico (New Spain), 1519-21, was aided by an epidemic of smallpox, which had dramatic effects on the native Aztec (or Nahua) population. Throughout the 16th century, many more epidemics continued to occur. However, there is one disease whose identity remains a mystery to scholars, even to this day: cocoliztli.

How catastrophic was disease in general?

There is a debate over how catastrophic the introduction of Western diseases really were on the immunologically naive natives of the Americas.

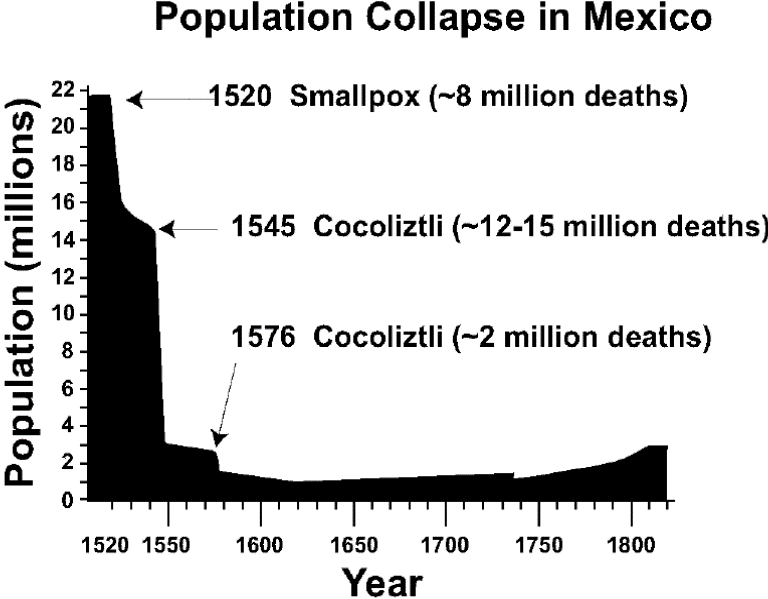

Historians in the 1960s, like Crosby and McNeill tend to highlight the destructive nature of disease, and statistical estimates by Cook and Simpson (1948) and Cook and Borah (1957) suggest that around 90% of natives had died by the end of the century. These arguments lean towards disease determinism.

However, more recently, this has been disputed, and more conservative estimates fall around 60-70%.

A graph showing the population collapse in Mexico, sourced from Acuna-Soto.

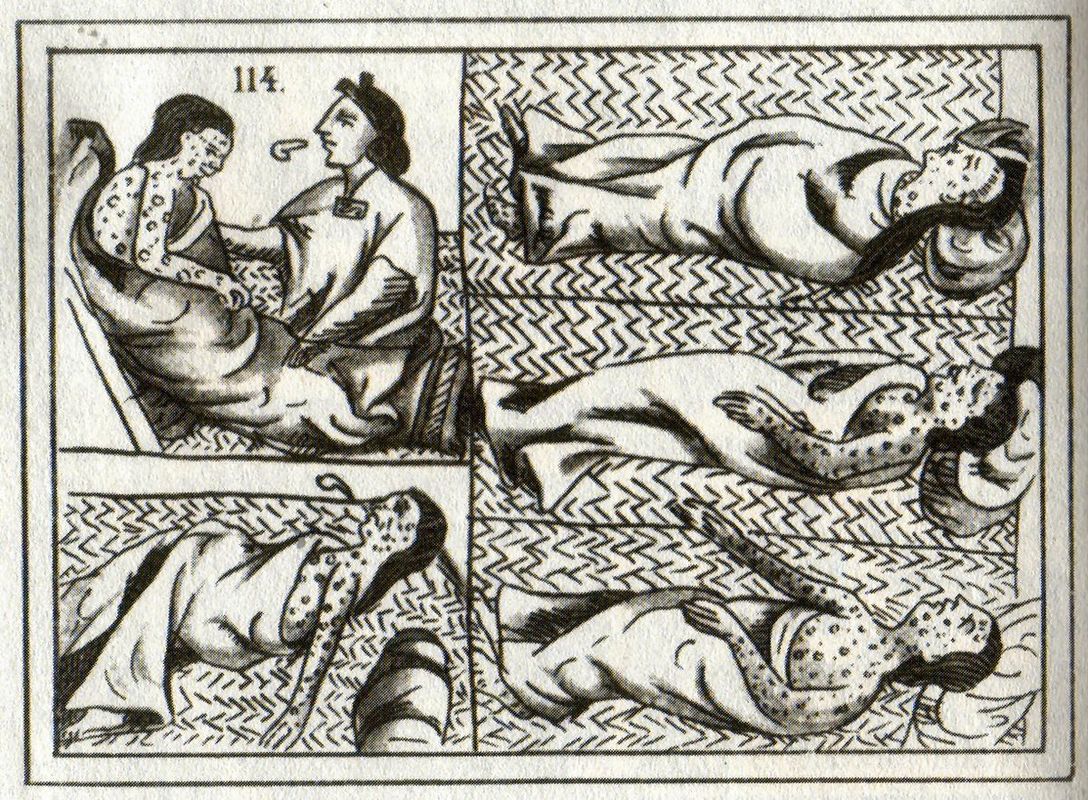

Native disease victims, from the Florentine Codex Book XII, folio 54 (compiled 1540-85).

What is cocoliztli?

During the 16th century there were two main cocoliztli epidemics: 1545-8 and 1576-80.

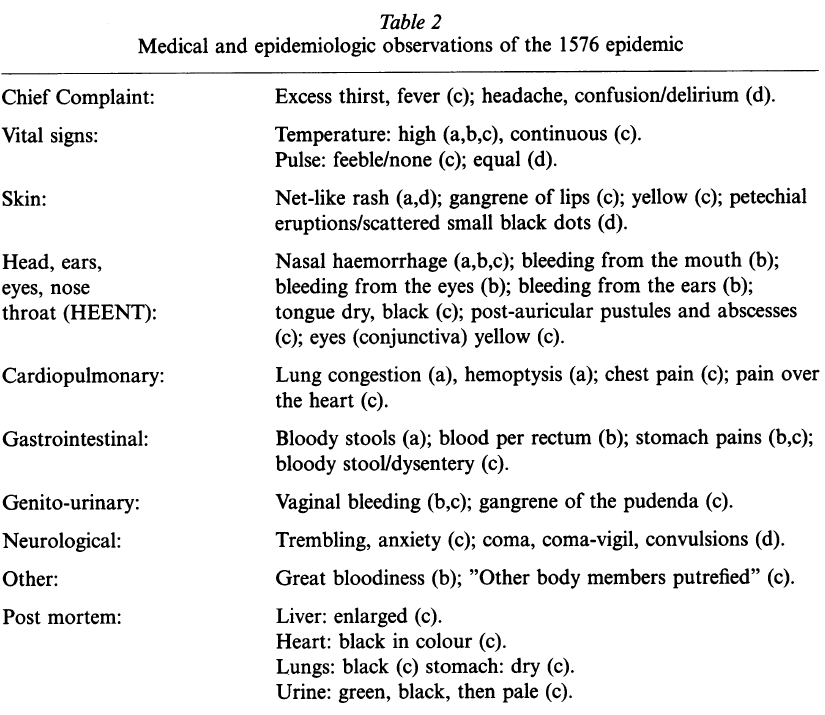

One of the issues with cocoliztli is the inability to match its symptoms with any of the established diseases of the time. Cocoliztli had ‘some degree of polymorphism’ due to the differing frequency of symptoms that were expressed/manifested. The course of the disease transmission for example in the 1576 epidemic, radiating outward from a source, mimicked other communicable diseases like smallpox and influenza, adding further confusion.

Historians have tried to identify cocoliztli, with suggestions including typhus, yellow fever, plague, influenza and smallpox, to name just a few. The emphasis was that the disease was imported from the West. However, Marr and Kiracofe's proposition that the disease was actually of native origin, has altered our perspective entirely.

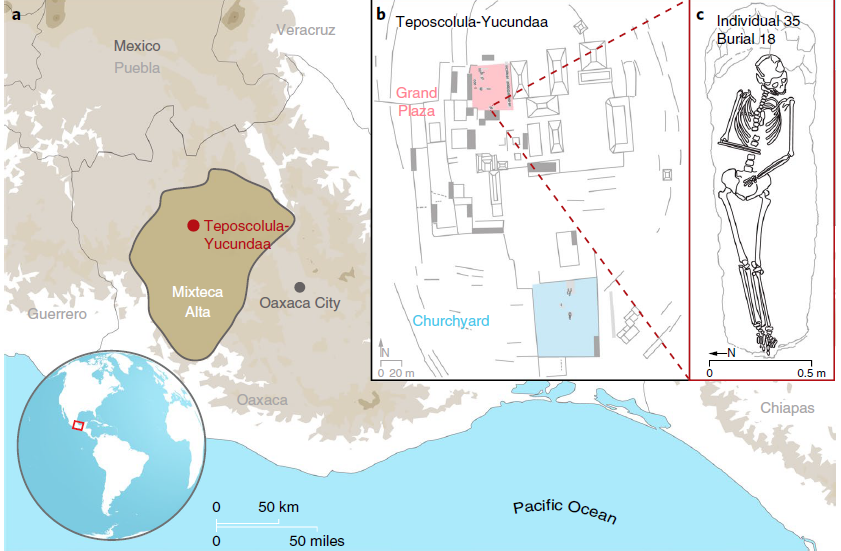

Recent archaeological discoveries in Mexico have also broadened the amount of sources that can be used to decipher the identity of cocoliztli. Excavation of a Mixtec cemetery located in Oaxaca provides vital physical evidence of the epidemic. Investigation into the site from 2004 has revealed a strain of salmonella enterica present. This find, linked to the discovery of the same strain in a 12th century skeleton in Norway, offers another possibility.

The Relaciones Geograficas

Table detailing the symptoms of the 1576 cocoliztli epidemic, sourced from Marr and Kiracofe.

Location of the grave excavation at Teposcolula Yucundaa, where traces of salmonella enterica was found.

What was my investigation?

My investigation was to analyse the way in which cocoliztli was addressed and portrayed in The Relaciones Geográficas of New Spain, to ascertain how disease was discussed, what causes there were, and if there were any cures. I would relate this to our current understanding of Nahua perceptions of health and the body, as well as contributing to the debate over the identity and deadly nature of cocoliztli.

One of the pinturas (maps) that was returned with the RGs, this particular one is from The Relación Geográfica de Meztitlán

The Relaciones Geográficas

The RGs are an example of just one of many attempts to collect information about the Spanish crown’s dominions. They are one of the many carefully composed and intentional surveys that were distributed across the Spanish colonies. Juan López de Velasco was appointed as Royal Chronicler-Cosmographer in October 1571 and was tasked with mapping the colonies. The first draft of the RGs is dated 25th May 1577.

The RGs are a set of 50 questions, split into sections. Questions 1-10 dealt with Spanish towns, 11-15 concerned native towns, 16-37 were directed towards inland communities, and opposing this, 38-50 requested information on ports and coastal communities. It also requested a pintura (map) of the area. This means the RGs offer a comprehensive view of life in New Spain at this point.

The questionnaire was distributed to the sub-units of territorial organisation - either corregimientos or alcaldías mayores. Due to the content of the survey, collaboration between natives and the Spanish was necessary. The RGs were completed and returned from 1579 to 1585.

Rene Acuna published an edited collection of ten of the RGs, whilst another two concerning Yucatan were published by Mercedes de la Garza. These are the documents I used.

Method

Due to the vast nature of the corpora, (to date there are 168 documents comprising of almost a million words!), it was not be feasible for me to read the entirety of the RGs. As such, I used Voyant Tools, a free web-based application. By using a machine ready corpora (provided by the Digging into Early Colonial Mexico project at Lancaster University - see Murrieta-Flores), Voyant Tools provided various ways for me to analyse the corpora.

Voyant allowed me to search for key terms, and retrieve all instances where this appeared within the corpora. I extended my search by using 'cocoliz*' and 'cocolix*', to cover spelling variations. I found that cocoliztli was also referred to as 'cocolizte(s)', 'cocoliztle(s)' and 'cocolixtle(s)'.

The home page of Voyant tools when the corpora has been uploaded, showing the wide variety of tools available to use to analyse corpora.

Findings

My findings so far can be divided into four main areas: depopulation, identity and origin, causes and cures.

Identity and Origin

The conflicting way cocoliztli is addressed – appearing only after the conquest yet being unfamiliar to Spaniards – could provide evidence to support scholars Marr and Kiracofe that propose that cocoliztli was an entirely new disease.

Despite discrepancies over when communities were afflicted with disease, the responses give the impression that the natives were healthier prior to the conquest, as an explicit example states, ‘vivieron antiguamente más sanos que ahora’. Thus, this would seem to suggest that cocoliztli only appeared after the Spanish conquest, which is confirmed in one entry as, ‘antiguamente, no sabían lo que era un cocoliztle’.

Yet, this does not automatically mean that the disease was imported, as the retention of the Nahuatl to describe the disease is notable. There are attempts to translate it, describing cocoliztli as being the equivalent to: ‘peste’, ‘pestilencia’, ‘enfermedades’ and ‘pestilencias generales’.

However, the retention of the word may suggest Spanish unfamiliarity with the disease, as they attempt to explain it to the reader. It may also suggest that there is something alien about the word or the disease which means that using solely the translation will not suffice. As Dufendach states, the continued use of cocoliztli to refer to disease emphasises the ‘unchanged indigenous conceptualisation’ of disease.

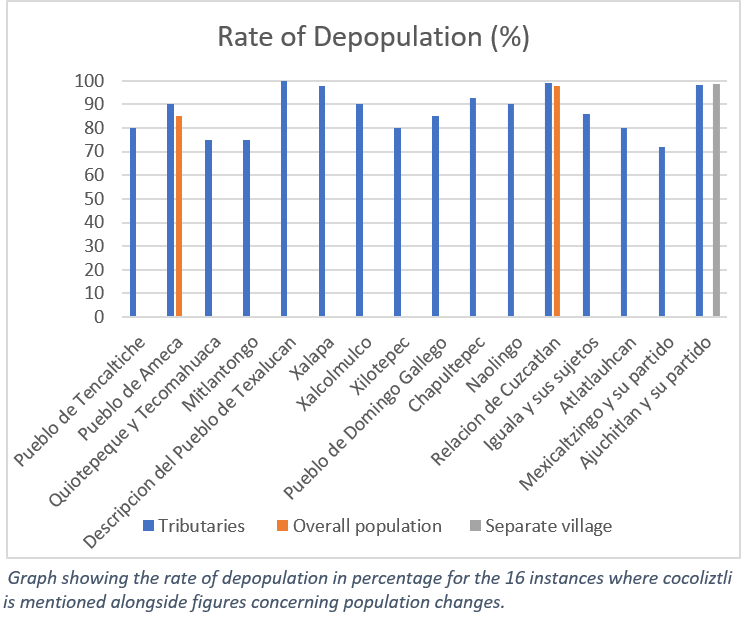

Depopulation

It is almost too obvious that depopulation and cocoliztli were inextricably linked, however it is a key relationship that has to be addressed. In the corpora, whenever cocoliztli is mentioned, the high rate of depopulation of the area is also mentioned. This is the most prominent trend that can be deduced, as 38 of the 54 references also refer to the depopulation of the area.

As the graph below shows, the smallest decrease was 72%, from the Relación de Mexicaltzingo y su partido, Mexico, from ‘más de dos mil’ to ‘quinientos y sesenta tributarios’. The largest decrease, 99.75%, occured in the Descripción del Pueblo de Texalucan in Tlaxcala, ‘habra en el dicho pueblo cuarenta indios vecinos, poco más o menos y que antiguaments solia haber en él dieciseis mil vecinos’.

Though these are only a few examples, it can indicate the depopulation levels certain localities were experiencing, yet should not be extrapolated to be considered representative of the entirety of New Spain.

Causes

Many areas note the condition of the land, which links to the fundamental concept of dualism that natives used to understand the cosmos in general, as well as health. Numerous adjectives were used to describe the condition of the land, 'tierra áspera, seca y fría y sana’, and each would have corresponding opposite pairs.

Air quality and wind was also a key cause. In the Relación de Iguala, the bad vapours, 'corrompen los aires'. For natives, the wind was an expression of the god of wind, Quetzacoatl, and had the potential to cause mass destruction. This could also be evidence of Spanish influence, as Hippocratic thought also considered wind to be harmful, depending on its temperature and quality.

As the Aztecs valued equilibrium and order, change in rituals and enviroment could also cause disease. Reorganisation and disruption of traditional native spatial community organisation was an issue for some. Those that remained after the encomendero Pedro de Escobar had sold others into slavery, ‘han pasados grandes pestilencias’.

An overarching theme is the condition or change of the environment in which the natives resided. However, there were also solely spiritual causes of disease, as cocoliztli is also attributed to being sent by God.

Cures

It could be concluded that part of the reason cocoliztli was so deadly ‘por no tener remedios con que atajar las enfermedades’. The natives appear to have been renowned herbalists in the corpora, ‘cúranse con yerbas porque muchos dellos son herbolarios’. It is thus very surprising that there was no remedy found for cocoliztli, prompting one to think that natives had not encountered this disease or a disease of this kind before.

Other methods of healing other than the use of herbs are also described. The nature of bloodletting prior to conquest is detailed, as they would ‘punzarse la cabeza, pechos y vientres’. Whilst the Spanish used bloodletting as a way of balancing the humours, to achieve physical equilibrium, natives approached bloodletting from a spiritual perspective, viewing it as a sacrifice. Phlebotomy was an offering to the gods, as according to the founding myths of the Aztecs they were in blood debt to the sun.

Conclusion

Overall, this poster has given an overview of the trends and information that can be extracted from the references to cocoliztli in the RGs. What can be deduced is a strong persistence of native Nahua beliefs in terms of health, but also an indication of the intertwining of native and Spanish ideas, whether voluntarily or imposed. Resultantly, glimpses into the embryonic hybridity of mestizo society are visible. A definitive answer cannot be given on the origin of cocoliztli; however, it seems that cocoliztli was not present before the conquest, and the term cocoliztli was used in different ways by different communities. Despite significant challenges in terms of the sparsity and reliability of data, insights into the truly devastating nature of disease were provided. As my research is ongoing, I suspect there will be many more deductions to make about cocoliztli. In regards to further research, cocoliztli and the RGs are continuing to be a topic of fascination and focus.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Acuña, René, Relaciones Geográficas del siglo XVI, 10 vols (Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, 1982-8)

de la Garza, Mercedes, Relaciones histórico-geográficas de la gobernación de Yucatán, 2 vols (Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Filológicas, Centro de Estudios Mayas, 1983)

Secondary Sources

Acuna-Soto, Rodolfo and others, ‘Megadrought and Megadeath in 16th Century Mexico’, Emerging Infectious Diseases, 8.4 (2002), 360-62

Cline, Howard, ‘The Relaciones Geográficas of the Spanish Indies, 1577-1586’, The Hispanic American Historical Review, 44.3 (1964), 341-74

Crosby, A.W., The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492, 30th edn (Westport: Praeger, 2003)

Dufendach, Rebecca, ‘Nahua and Spanish Concepts of Health and Disease in Colonial Mexico, 1519-1615’ (Doctoral dissertation, University of California, 2017)

Lockhart, James, The Nahuas After Conquest: A Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth through Eighteenth Centuries (California: Stanford University Press, 1992)

Marr, John S. and James B. Kiracofe, ‘Was the Huey Cocoliztli a Haemorrhagic Fever?’, Medical History, 44 (2000), 341-62

McNeill, W.H., Plagues and Peoples (Oxford: Blackwell, 1977)

Mundy, Barbara E., The Mapping of New Spain: Indigenous Cartography and the Maps of the Relaciones Geográficas (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996)

Murrieta-Flores, Patricia, Diego Jiménez-Badillo, and Bruno Martins, ‘Artificial Intelligence, Computational Approaches, and Geographical Text Analysis to Investigate the History of Early Colonial Mexico’, Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Latin American History, (2021 -In Press) 1-29

Vågene, Åshild J. and others, ‘Salmonella Enterica Genomes from Victims of a Major Sixteenth-Century Epidemic in Mexico’, Nature Ecology and Evolution, 2 (2018), 520-528

Warinner Christina, and others, ‘Disease, Demography and Diet in Early Colonial New Spain: Investigation of a Sixteenth-Century Mixtec Cemetary at Teposcolula Yucundaa’, Latin American Antiquity, 23.4 (2012), 467-489

Slide 1 image (max 2mb)

Slide 1 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 1 Caption

Slide 2 image (max 2mb)

Slide 2 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 2 Caption

Slide 3 image (max 2mb)

Slide 3 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 3 Caption

Slide 4 image (max 2mb)

Slide 4 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 4 Caption

Slide 5 image (max 2mb)

Slide 5 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 5 Caption

Slide 6 image (max 2mb)

Slide 6 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 6 Caption

Slide 7 image (max 2mb)

Slide 7 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 7 Caption

Slide 8 image (max 2mb)

Slide 8 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 8 Caption

Slide 9 image (max 2mb)

Slide 9 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 9 Caption

Slide 10 image (max 2mb)

Slide 20 video (YouTube/Vimeo embed code)

Image 10 Caption

Caption font

Text

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)

Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Image description/alt-tag

Image caption

Image link

Rollover Image (max size: 2mb)

Or drag a symbol into the upload area

Border colour

Rotate

Skew (x-axis)

Skew (y-axis)