Zacharie Chiron

My dissertation research centres around agapē, a Greek concept referring to unconditional love, found in the New Testament and other Christian literature. I explore implications of agapē as an ethics, and what distinctive focus it yields within the frameworks of virtue ethics (based in the character traits that one ought to develop) and utilitarianism (put simply, the most good for the most people). My approach is philosophical and critical: I look at several philosophers who have discussed agapē, from Aquinas to modern authors such as William Greenway, in combination with my own understanding, to assess how ethical theories are shaped if centred around agapē. I make three main arguments. The first contributes to an academic debate about the usefulness (or lack thereof) of virtue ethics in terms of guidance: I contend that agapē provides much needed unity and direction to the virtues. Secondly, I argue that agapē saves utilitarianism’s impartiality from being alienating. Finally, addressing an area insufficiently explored in the literature, I propose that agapē ethics proves more applicable to the real world, through both its motivational force and its ability to combine teachings from virtue ethics and utilitarianism

Zacharie Chiron

Chapter 1 - The Agapist as the Virtuous Person

Virtue Ethics, as an ethical system, attempts to be closer to our intuitions and psychology, as well as provide more practical guidance than other systems, by focusing not on maximising something like happiness, nor on following rules, but on virtues, i.e. character traits, that we should develop. Once those character traits become second nature, acting virtuously or morally will become intuitive. Eric Silverman, in his 2019 book The Supremacy of Love: An Agape-Centered Vision of Aristotelian Virtue Ethics, makes a case for agape - unconditional love - to be at the centre of virtue ethics, for agape to be the directing virtue. From Plato to modern psychologists like Jonathan Haidt, it is recognised that love has great power and is of utmost significance.

Silverman builds his agape-centered virtue ethics (henceforth, AVE) on Thomas Aquinas’ system, but independent from the theological background. Aquinas thinks the virtues, the good character traits that we ought to develop, can be derived from four ‘cardinal virtues’: prudence, temperance, courage/fortitude and justice. At the centre of all the virtues is agape, which is to shape the end of the

virtues. In other words, all the other virtues should be practised with the goal and intent of being loving. Having such a framework is beneficial for agape ethics. Indeed, oftentimes the agent wishes to act lovingly but does not know how. We can picture a young parent not knowing how to deal with their crying baby. In order to be the most loving possible, they need to have developed virtues such as patience and understanding.

How does agape provide a distinctive ethical focus in virtue ethics? It does so in two primary ways: it is distinctive in direction, and distinctive in scope. A common criticism of virtue ethics is that the system

lacks direction and that the virtues lack unity; they can be discordant with each other. For example honesty may call one to divulge an offensive truth, while tenderness may recommend not to offend. How is one to know which virtue to follow? In AVE, agape directs the agent. The other virtues must be practised with the end, the goal, of agape. Agape can therefore act as an arbiter between honesty and tenderness. Hence, one will consider what is most loving towards the people involved, and depending on the circumstances, this may be to follow honesty, or tenderness. The agape virtue ethicist thus benefits from the general advantages of being used to being honest and tender, while having the overriding guidance of agape love.

Agape also generates a virtue ethics distinctive in scope: agape being unconditional, it is directed to everyone without conditions of proximity, relationship status, kindness of the person, gender, race, nationality, social class or anything else, including species, as I argue along with William Greenway. This is notably distinctive from the virtue ethics of Aristotle, perhaps the most famous virtue ethicist, since Aristotle limits the range of actions required by justice to those that affected members of one’s political community, thus excluding people outside this community.

Aristotle (left) and Aquinas (right)

Chapter 2: The Agapic Calculation

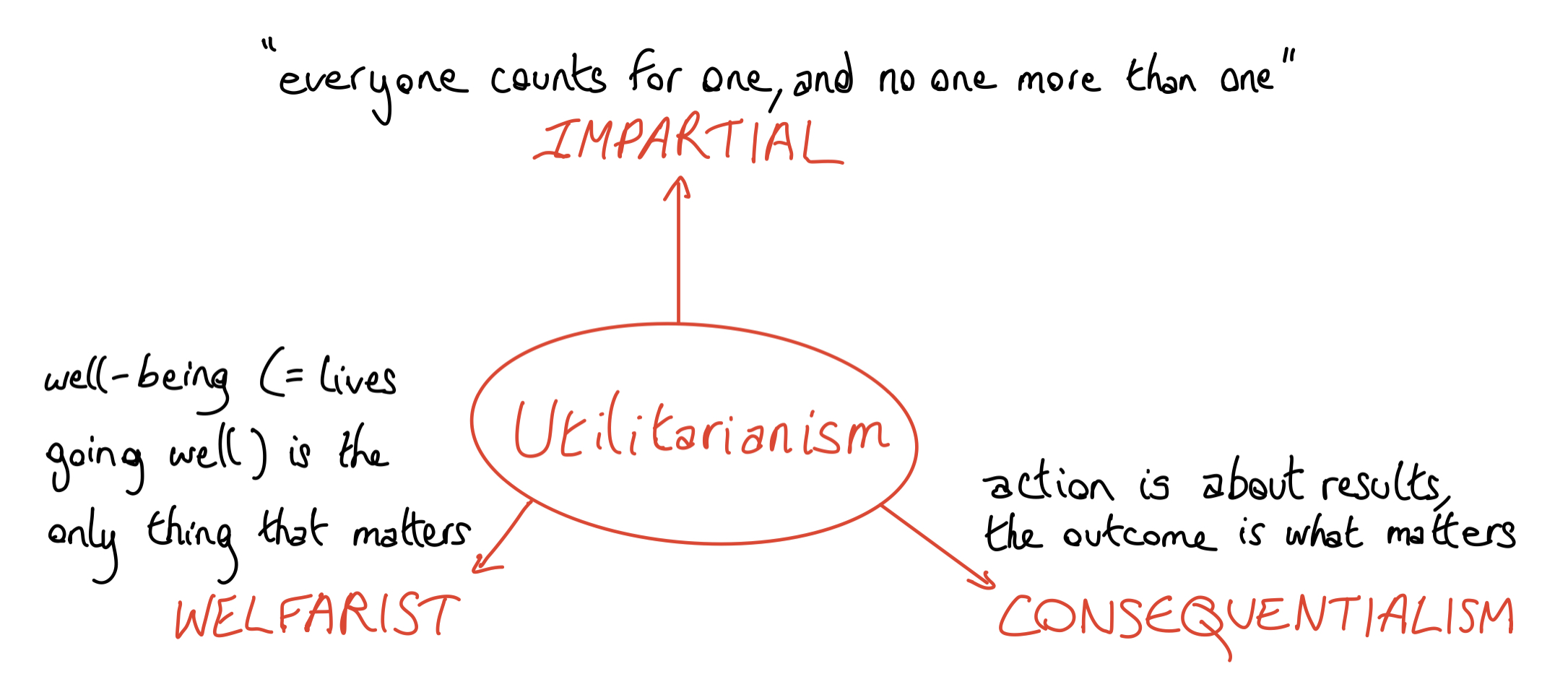

You may have heard of Joseph Fletcher’s situation ethics. Fletcher thinks that one ought always to do the most loving thing, and that any other rule, law or custom can offer illuminative guidelines, but never direct us. In other words, whenever a rule commands us to act in a way that is not the most loving, we should not follow the rule. This may seem very similar to the utilitarian framework, which calls us to do what maximises well-being (often simplified to happiness). For the utilitarian, other rules, institutions or values will similarly be upheld only if they maximise well-being. Thus, is agape ethics utilitarian? And if so, does agape provide a distinctive ethical focus to utilitarianism?

Utilitarianism is defined by Sam Clark in his 2015 research report on Ethical decision-making as “impartial well-being consequentialism”. Agape is definitely impartial. Gene Outka, in his 1972 book Agape: An Ethical Analysis, explains that agape implies the principle of equal-regards: one should love everyone equally and without

discrimination. As Silverman clarifies, this does not mean that everyone should be treated in exactly the same way, since circumstances and relationships might lead us to have more trust or additional responsibilities towards certain people, for example. But it does mean that there can be no arbitrarily differential, or preferential, treatment. Outka defines agape as “an active concern for the neighbor’s well-being which is somehow independent of particular actions of the others”. The independence from particular actions of others reflects agape’s unconditionality; it is not conditional on others’ actions. Outka’s definition also helps us see that the primary focus of agape ethics is on the well-being of people, like utilitarianism. Whether only well-being is valued, and whether purely the consequences of actions matter in deciding how to act (and not, for example, how people have been treated to bring about that good), is contentious and disputed in the agape literature - I explore this more in my dissertation. If one follows Fletcher with Outka’s definition of agape, however, it seems as though agape ethics will be impartial well-being consequentialism, making it a form of utilitarianism.

How is it a distinctive utilitarianism, then? Agape-centered utilitarianism (henceforth, AU) makes a claim about what constitutes well-being: to love and to be loved are paramount. This is in line with Hegel’s idea of a “struggle for recognition,” recognition being what all ultimately desire, and being loved being the ultimate form of recognition. This is also reinforced by countless studies that show that love is absolutely essential, notably for childhood and the growth of a stable individual, with lack of love generating issues like borderline personality disorder or

emotional deprivation disorder. AU also resolves the alienation that utilitarianism’s impartiality can generate. Indeed, while agape is impartial, it recognises the importance of proper relational bonds and the responsibilities that emerge from certain relationships, and therefore recognises the importance for an individual to take care in special ways of their close ones. Finally, AU is distinctively empathetic. In its goal to maximise well-being, it puts an emphasis on the daily acts of love that fill surrounding people with warmth.

Chapter 3: Ethics in the Real World

Agape is distinctive in yet another way: its applicability to daily situations as well as moral dilemmas and life-long decisions. Notably, agape accommodates well ethical teachings from both the virtue ethics and the utilitarian traditions. Since AU acknowledges the importance of being loving in maximising well-being, it recognises the crucial benefits of cultivating the virtues supported by AVE, such as the cardinal virtues and other character traits that flow from them, like tactfulness from prudence and self-control from temperance. The virtues help the agent in maximising well-being. For example, practical wisdom (phronesis, in Greek) helps the agent intuitively know what to do in some situations, thus saving the time and effort of calculating and decision-making. As such, agape provides us both with a long-term direction, i.e. cultivating the virtues that will allow us to be most loving; and with a decision-making procedure to use in the moment, i.e. maximising well-being.

Finally, agape provides distinctive motivations to act morally. Silverman, in his 2009 book The Prudence of Love: How Possessing the Virtue of Love Benefits the Lover, outlines multiple relational and psychological benefits of love, and explains how possessing a loving disposition more reliably increases one’s happiness than possessing an unloving disposition. But beyond that, agape also provides grounds to overcome the

common modern moral relativism that is often at the origin of moral skepticism, the idea that no one has any moral knowledge, which can often lead to positions such as that there is no right or wrong.

One of those grounds is that explained by Greenway, in his 2016 book Agape Ethics: Moral Realism and Love for All Life. Greenway identifies that we all experience instances of being seized by love for others (including non-humans); for example when you see someone being unjustly treated in front of you and that you can feel it boil inside, or when you see a child chuckle in joy and feel warmth

inside. All of these instances reveal a reality that you are being seized by love for these beings, which is not a subjective opinion, but a moral reality. These instances of being seized by love, of agape, ground morality. What is right is then to respond appropriately to this being seized, and what is wrong is to harden one’s heart to being seized, or refuse to respond to being seized, by love for all beings.

Conclusion & The Kindness Boomerang

In brief, agape provides a distinctive ethical focus to virtue ethics in both scope and direction, resolving issues such as the lack of coherence between the virtues, and it provides utilitarianism with more empathy and day-to-day love as well as relief from the issue of alienation. Finally, agape ethics is more usable in practice as it can accommodate useful teachings from both virtue ethics and utilitarianism, and it provides strong motivations for morality. To conclude, let us see an illustration of agape love. Check out the Kindness Boomerang below.

Also, this research is of great interest to me beyond academic curiosity, as I try to implement agape ethics in my daily life. Please feel free to contact me for any thoughts, comments or questions regarding my dissertation research, agape, agape ethics or ethics more generally, at zacharie.chiron@gmail.com

Acknowledgments

My first thanks go to my dissertation supervisor Professor Alison Stone for her active, regular and reliable support throughout the whole of this endeavour. Secondly, I thank my dear friends Nathaniel Peutherer, Jamie Walls, Joel McBeath and in particular Callum Goode, as well as Professors William Greenway and Eric Silverman, for the discussions with them that shaped my understanding of agape and agape ethics. I am also grateful to all the members and supporters of The Agapic Project without whom the venture would not have been possible; it has made me grapple with multiple practical concerns relating to agape ethics. There are many more that I cannot name here, but my final thanks go to my parents Laurie and Yannick Chiron who have shaped me to become the person I am and given me assets to reach the place where I am now, as well as my sister Gabrielle for her relentless support.

Key References

Floyd, S. (2020) Thomas Aquinas: Moral Philosophy. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ISSN 2161-0002. Available at: https://www.iep.utm.edu/aq-moral/#H3 [Accessed 17 October 2020].

Greenway, W. (2016) Agape Ethics: Moral Realism and Love for All Life. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books.

New World Encyclopedia (2019) Agape. Available at: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Agape&oldid=1017946 [Accessed 8 November 2020].

Outka, G. (1972) AGAPE: An Ethical Analysis. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Silverman, E. J. (2019) The Supremacy of Love: An Agape-centered Vision of Aristotelian Virtue Ethics. [Online]. Kindle. Available at: https://a.co/hSJpwvv